| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

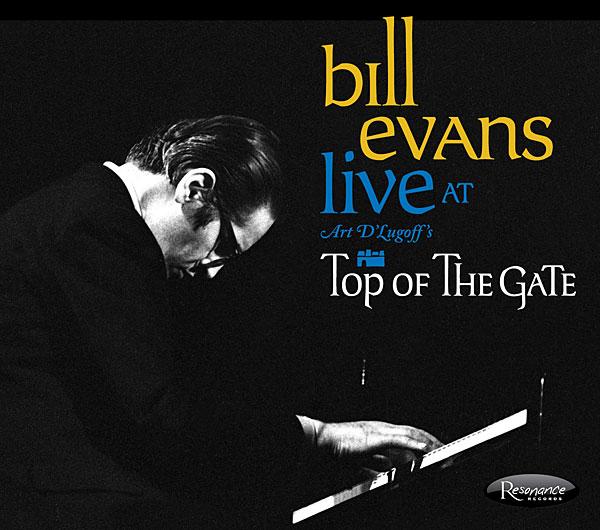

Recording of July 2012: Bill Evans Live at Art D'Lugoff's Top of the Gate

Bill Evans: Live at Art D'Lugoff's Top of the Gate

Bill Evans, piano; Eddie Gomez, bass; Marty Morrell, drums

Resonance HLP-2012 (2 LPs/2 CDs, HDTracks 24/44.1k download). 1968/2012. George Klabin, exec. prod., mix, sound restoration; Zev Feldman, prod.; Fran Gala, mix, sound restoration, mastering. ADA/ADD. TT: 49:12/40:50

Performance *****

Sonics * to ***

Bill Evans, piano; Eddie Gomez, bass; Marty Morrell, drums

Resonance HLP-2012 (2 LPs/2 CDs, HDTracks 24/44.1k download). 1968/2012. George Klabin, exec. prod., mix, sound restoration; Zev Feldman, prod.; Fran Gala, mix, sound restoration, mastering. ADA/ADD. TT: 49:12/40:50

Performance *****

Sonics * to ***

Complain if you will, analog lovers, about the evils of digital technology, but in one area there isn't a whiff of argument: the esoteric pursuit of rescuing live recordings with marginal sound. Without question, manipulating ones and zeros has cleaned up a lot of nearly unlistenable bootlegs. This bit of buried treasure, while never unlistenable, has been rendered in sound that is, at times, very good. The two-star sonics rating, which may seem shocking for a "Recording of the Month," is an average—while the sound quality rates a single star in the opening, it's nearly up to four stars by Disc 2. The long-ago sounds of these two live sets of the Bill Evans trio playing mostly standards, recorded in a long-gone Greenwich Village club, Top of the Gate (it was literally above the better-known Village Gate jazz club), are, if not the holy grail, then a very gilded cup.

With the release of this and, earlier this year, Wes Montgomery's Echoes of Indiana Avenue, Resonance Records has been transformed from a mid-level jazz label signing new artists to a splashy reissue house specializing in unearthing previously unheard live sessions. George Klabin, who owns Resonance, was 22 when he recorded these sets, on October 23, 1968. According to his liner note in the booklet that accompanies the CD and LP editions, Klabin used four microphones: for Evans's piano, a Neumann U67; for the drums and split left, a Beyerdynamic and a Sennheiser condenser; and an Electro-Voice dynamic mike wrapped in foam, taped to the bridge of the double bass, and split right in the mix. These fed a Crown two-track tape recorder that could run at 7.5 or 15ips. Without a chance to check levels and find a balance, Klabin did the stereo mix on the fly, which accounts for the wobbly mix and the too-prominent bass in the first two tracks, "Emily (take 1)" and "Witchcraft." Overall, the sound improves as you go along, and by the second set is much improved.

In his liner note, Klabin recounts his recording philosophy: "In the 60's many recordings of jazz that I heard lacked presence and definition, since the mikes tended to pick up too much room sound and leakage of the other instruments. However, there is always a risk of distortion when placing a mike close to a loud instrument like drums, which is one reason that engineers during this period preferred to mike at a distance. The intimacy and detail that you hear on this recording are due to my close mike choices, and I think the recording compares favorably with today's recording techniques."

Musically, any unreleased, undiscovered Bill Evans is an event of note—and especially this year, which marks the 83rd anniversary of his birth (Evans died in 1980, at 51). On these two discs, in a fortuitous conflux as the sound quality improves, so does the intensity of Evan's playing. Crowd noise is kept to a minimum throughout. The 180 gram, Bernie Grundman mastered, RTI-pressed LPs are incredibly quiet.

Evans's bandmates that night were bassist Eddie Gomez and drummer Marty Morrell—the trio had been together only for several weeks when these recordings were made. While they provide admirable support—particularly Gomez, whose playing was always strongly simpatico with Evans's vision (though not as strong as that of the great and, by 1968, late Scott LaFaro)—the leader's playing remains a wonder to behold. The quality of the ideas that flowed from his brain to his hands is unmatched in the history of jazz piano. Never the flashiest nor the loudest player, Evans had a quiet grace and an exquisite impressionistic touch that to this day remain unequaled. Just as Frank Sinatra made well-worn, oft-recorded standards his own, Evans's way with tunes like Cy Coleman's "Witchcraft" (also memorably covered by Sinatra), or an oddly upbeat, at times nearly unrecognizable version of Joseph Kosma's "Autumn Leaves," made these familiar melodies, if not his own, then a proprietary corner of the jazz canon.

Although Evans's greatest gift may have been his sense of timing and the sentimental, bittersweet edge he could add to ballads—though here he choose mostly upbeat numbers—he also had an astonishing way with the current songs of the day, particularly TV and movie themes. His unforgettable reading of Johnny Mandel's "Suicide Is Painless," from M*A*S*H, was a highlight of his later career. Here he breezes through Burt Bacharach's "Alfie" with a light touch and the kind of short, rhythmic leaps forward that marked him as a master reinventor of well-known material.

Condemned by some jazz fans as too laid-back and too self-referential, Evans, who played on Miles Davis's Kind of Blue and even wrote that album's liner notes, was a musician of uncommon gifts—as is proved yet again by this extremely welcome artifact.—Robert Baird

- Log in or register to post comments