| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Recording of January 1983: The Art of the Transcription

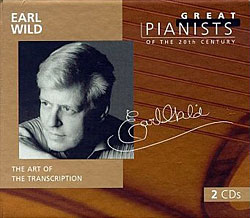

EARL WILD: The Art of the Transcription

EARL WILD: The Art of the TranscriptionEarl Wild, piano, recorded live at Carnegie Hall on November 1, 1981

Audiofon 2008-2 (2 LPs). Julian Kreeger, prod., Peter McGrath, eng. AAA

It takes nerve for a performer to allow an entire concert to be recorded for release on disc. It also takes extraordinary confidence in one's technique. Mistakes that are overlooked in the live experience become snags for the ear in the recorded version. One starts to listen for them and loses the musical experience in its totality.

This is one reason why so many discs are mastered in the recording studio or in an environment without listeners. But the result of this is that the performances lose impetus and enthusiasm, and sound played by rote. The audience can inspire an artist to great heights. The sterile environment of the studio cannot (footnote 1). If you have any doubts, listen to this recording of Earl Wild's concert at Carnegie Hall.

Most of this recording was done at a concert given on November 1, 1981, although the jacket notes state that "minor portions were rerecorded following the concert." Audience coughs are evident during the quieter passages, and there is applause at the end of the selections, which contributes to the illusion of being there.

Mr. Wild's performances are striking in both interpretation and technique. His choice of transcriptions for piano allows him ample room to display both his technical virtuosity and his stunning interpretations of the Romantic period for which he is so justly noted. Beginning with Sgambati's 19th-century transcription of Gluck's Melodie d'Orfée and ending with the Shulz-Evler piano version of themes from Strauss's The Beautiful Blue Danube, each selection reveals a different facet of transcription, as well as Mr. Wild's extensive knowledge of piano repertoire.

The Gluck, with its singing lines, is followed by Leopold Godowsky's transcriptions of three pieces by Rameau. The piano can never imitate the harpsichord; the tonal structure is simply too different. And I must confess that I miss the twangy bass that is so characteristic of French harpsichord music of that period. But Godowsky has managed to retain the integrity of the originals in these piano versions. The Rigaudon and Elegie fare the best. The familiar Tambourin seems to suffer somewhat in translation.

These 18th-century works are followed by Tausig's arrangement of Bach's Toccata and Fugue in d. I cannot hear this without thinking of Stokowski's arrnagement for orchestra that opened Walt Disney's movie Fantasia, but this piano version does not suffer by comparison. I did feel that the climax seemed to be a trifle lacking in dynamic range. This might be attributed to the recording, but I think it is more likely due to the fact that a piano has no pedal notes as does the organ. The technical demands are great, and the Fugue is enlightening in its harplike arpeggiation. Mr. Wild handles the complex fingering demands—a mere bagatelle for him— with ease.

The Moszkowski arrangement of Isoldens Tod from Wagner's

The last Rachmaninoff transcription is of the Scherzo from Mendelssohn's A Midsummer Night's Dream. Not only is this another virtuosic masterpiece, but it's lots of fun.

Sigismond Thalberg is one of those pianists who was well-known in his day but now, despite many compositions, is almost unrecognized. He is noted for his development of a type of composition which allows the thumb to play the melody while the other fingers are devoted to arpeggios, chords, and runs, thereby giving the illusion of playing with three hands. It is significant that this development has been attributed to Franz Liszt; perhaps that is why Thalberg has been forgotten. Liszt once said "Thalberg is the only pianist who can play the violin on the piano." This ability is what gives Thalberg's Grande Fantasie sur l'Opera Semiramide its great interest and, incidentally, allows Mr. Wild to exploit his great interpretive powers.

Liszt's arrangements of three Polish songs by Chopin are light and tuneful, a pleasant change of mood after the rather high-powered Rossini-Thalberg. Liszt seems to have added very little of himself in these, and the distinguishing ornament-like bass of Chopin shines through.

Earl Wild's own transcription of the "Pas de Quatre" from Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake is a brief minute and a half. Not only is it charming, it elicited deligted chuckles from the audience. Wild's final work, the Shulz-Eveler Concert Arabesques on Themes of the Beautiful Blue Danube can only be called elegant. A perfect way to end a concert.

Except for that one occurence of pre-echo, I could find nothing about the recording to fault. it is not the highest-powered piano recording one could find, but it is a superb simulation of live-performance, concert-hall piano sound. This certainly is a state-of-the-art LP and deserves to be in the Top-of-the-Pile. It is also a serious contender for a Defintive-Disc Award. A must for any pianist or any lover of the piano repertoire. Mr. Wild has used his interpretive and technical pw0oers to give us a view of some little-known and too-often-ignored facets of the piano repertoire, and Audiofon has given us a memorable recording of the occasion.—Margaret Graham (footnote 2)

Footnote 2: Margaret Graham was the non-de-plume of J. Gordon Holt's wife, Polly.

Footnote 1:. The fact that MG discusses the benificence of audience-performer interaction in the same issue in which an editorial on the same subject appears has nothing to do with collusion or coincidence. It happened because both of us read the jacket notes of another LP reviewed in this issue (Syrinx 0977-011), which described their apparently unique approach to recording.—J. Gordon Holt

- Log in or register to post comments