| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Recording of February 1988: The Moscow Sessions

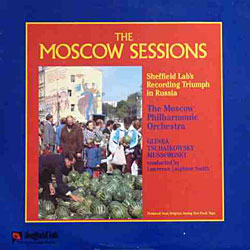

The Moscow Sessions

The Moscow SessionsBarber: First Essay for Orchestra; Copland: Appalachian Spring; Gershwin: Lullaby (for string quartet); Glazunov: Valse de Concert in D; Glinka: Russlan and Ludmilla Overture; Griffes: The White Peacock; Ives: The Unanswered Question; Mussorgsky: Khovanshchina Prelude; Piston: The Incredible Flutist (ballet suite); Shostakovich: Symphony 1, Festive Overture; Tchaikovsky: Symphony 5

Lawrence Leighton Smith, Dmitri Kitayenko, Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra

Sheffield Lab CD-1000 (3 CDs); TLP-1000 (3 LPs). CDs DDD. LPs AAA. TT: 180:40

The ecumenical collaboration between Sheffield Lab, the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra, conductors Lawrence Leighton Smith and Dmitri Kitayenko, an imposing gaggle of businessmen and bureaucrats, and partial sponsorship by The Absolute Sound's Fund for Recorded Music, if somewhat short of epoch-making, is, nonetheless, a positive example of free enterprise and socialism bedding down together, liberally (pardon the expression) lubricated with glasnost. Art, we are told, is universal. It transcends philosophical, racial, political, and religious differences of opinion. Yet, despite the implied altruism of this international cooperative effort, the actual genesis of the project was essentially pragmatic, fundamentally bottom line.

In Stereophile's April/May 1987 issue (Vol.10 No.3), Sheffield Lab's Lincoln Mayorga and Doug Sax, in conversation with J. Gordon Holt, disclosed that the soaring cost of recording American orchestras virtually forced the enterprising duo to seek cheaper, if not necessarily greener, pastures. Whatever the motivation, a recording of an American conductor directing a Soviet orchestra in Russian music, juxtaposed with a Soviet maestro interpreting Copland, Gershwin, Barber, etc., sounds promising and, we are told, is a first.

The Moscow Philharmonic is, of course, no stranger to US record collectors. Under the baton of Kiril Kondrashin (among others), their Melodiya recordings, mainly released by Angel here (and now Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab), made a great contribution to Shostakovich enthusiasts (of which I am one) with an almost complete discography of the 15 symphonies. By most accepted musical standards, the Moscow band is a fine ensemble on a par with the acclaimed Leningrad Philharmonic, but ranking, perhaps, lower than the Ministry of Culture Symphony.

As with all Russian orchestras, the perceptive listener may hear subtle differences of instrumental tone. Lawrence Leighton Smith points out in his notes that Russian horns play with a marked vibrato (particularly noticeable in the Tchaikovsky), their oboes have a darker sound, and, as their cellos' end-pins are both longer and angled unusually by American standards, the sound projection strikes the US listener's ear rather differently. I would add that Russian brass and woodwinds emit a somewhat coarser, earthier sound that invariably appears less studied and more spontaneous than that of their US counterparts. The strings, too, are weightier, less silky, and more plangent. Under the leadership of both Smith and Kitayenko (the orchestra's music director), homogeneity and balance are wholly admirable, and the rank-and-file musicians appear to be thoroughly involved emotionally with their duties. Of course, these recording sessions were embossed with an extraordinary sense of occasion which must have stimulated all concerned.

Lawrence Leighton Smith, presently music director of the Louisville Orchestra and the Music Academy of the West, Santa Barbara, California, is an extremely accomplished musician whose talents merit far greater recognition via both the concert hall and the recording studio. A musician's musician, Smith is one of a coterie of gifted American conductors (Los Angeles's Daniel Lewis is another who comes to mind) who frequently languish in the boonies making beautiful music, while lesser mortals overflowing with charisma and/or expensive PR guidance conduct major orchestras in minor recordings.

The Moscow Philharmonic is probably capable of playing Shostakovich, Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky, et Russian al, in their sleep. However, Smith's overview of the 18-year-old Shostakovich's first symphony, a student composition, is, in its own way, as impressive as Kondrashin's despite different emphases. After a jaunty, appropriately light-hearted opening Allegretto which captures the requisite quizzical buoyancy and sets the stage for things to come, he settles down to a more expansive, thoughtful reading. Shostakovich's omnipresent wit is graciously underlined, yet heavy doses of "subtle" effects are not allowed to overpower and smother compulsive piquancy. Transitions of tempi variations and mood are allowed to occur naturally, leading to a moving, integrated, synergistic totality.

I am less enthusiastic about the performance of the Tchaikovsky Fifth. If you like your Tchaikovsky with a surfeit of Sturm und Drang, this version may please you. Although Smith succeeds in controlling the orchestra's seemingly natural exuberance—possibly over-stimulated by that sense of occasion—for the Shostakovich, he appears to be waging a losing battle in the Tchaikovsky. In the aforementioned JGH article, Doug Sax was quoted as saying that this Fifth was "positively stunning, that this is the most impassioned, moving performance of this work you've ever heard." Well, I find it stunning, but not in the same sense. I have heard many interpretations far less emphatic, far less overwrought, yet infinitely more persuasively moving. Tchaikovsky created a passionate score; the intensity of emotion is all there in the notation. The last thing it needs is such overemphasis and underlining. With apologies to Mr. Sax, whose opinion could be nonobjective, if I wish to be stunned I'll climb in the ring with Mike Tyson.

I am impressed by Smith's reading of the Glinka and Shostakovich overtures. Similarly, the Khovanshchina by Mussorgsky, played with idiomatic elan, whetted my appetite for more of this melodious opera from these performers. Having long championed the cause of Alexander Glazunov, whose estimable symphonies are inexplicably ignored in this country—although they have begun to appear in recordings on such European labels as Olympia, Orfeo, and Chandos—I am thankful for small mercies, even for the Concert Waltz No.1, a pleasant but distinctly minor piece. This Slavic equivalent of a Strauss waltz is liltingly played with terpsichorean elegance.

For reasons solely musical, I am distinctly disenchanted by Kitayenko's plodding attempts to communicate the American musical idiom. True, he was apparently unfamiliar with this repertoire prior to having been given the scores by the Sheffield Lab people. One assumes from his obvious lack of sympathy with these pieces that he was not provided with records or tapes to familiarize himself with, at least, a requisite musical milieu. He sounds remarkably ill-prepared. Copland's evocative Appalachian Spring, for example, has had an international concert-hall life for years and exists in several helpful recordings. In his notes, Smith talks about hearing his Soviet colleague rehearsing and playing with what he describes as "a Russian accent." Methinks that maestro Smith is being ultra-tactful. Kitayenko's halting phrasing is four-square, his accentuation is sometimes out of whack, the playing, so boisterous in the Tchaikovsky, is tentative, and the artistic communication is at a low and distinctly un-American level.

Walter Piston's The Incredible Flutist, a charming ballet score seldom programmed these days, emerges a trifle more successfully but hardly offers competition to the excellent Louisville Orchestra recording with Jorge Mester conducting, or Howard Hanson's Mercury version. I'm afraid that I cannot honestly be more enthusiastic about Kitayenko's other American excursions.

As Sheffield Lab is the champion of direct-to-disc, it may surprise some fans that they decided to record digitally for CD release, and via two-track analog for LP. Obviously, marketplace dictates were largely responsible for this decision. As my realm of analysis and opinion is music, I don't intend to dip even my little toe in the waters of contention that surround the analog vs digital debate. In several decades of reviewing concerts and recordings, I still have not heard any music reproduction to completely capture the sound quality of a good seat in a fine, audience-filled concert hall. Methinks I never will. In sum, for me, a recording is to a live performance what a motion picture is to a play: they are similar but different art forms offering similar yet disparate aesthetic experiences.

That, succinctly, is my audio credo. In general, I am impressed with Sheffield Lab's engineering; they appear to have chosen music rather than audio impressionism as their end-product. Their digitally engineered CDs are notable for pristine clarity, expressive dynamic range, and exciting transients. As with many of their ilk, I am conscious of some sterility in the actual musical quality of the sound, but this seems to be endemic to a great deal of digital engineering. This also manifests as coolness in the sound character. Conversely, the analog LPs offer amiable warmth, rather less impressionable transients, and more natural-sounding string reproduction. I do not have keen preference for one over the other, but do confess to playing the CDs more often than the LPs. This, I admit, is probably due more to laziness and the CDs' undoubted convenience. Both recording methods serve their musical content admirably.—Bernard Soll

- Log in or register to post comments