| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Readers Review Stereophile's Poem LP Joint First-Prize Winners

Joint First-Prize Winner

Bernard Shaw, in correspondence to The Musical Digest for 1948, described Prokofiev's Flute Sonata, the principal work here, as "a humorous masterpiece of authentic violin music." Apparently that keen-music-critic-turned-dewy-eyed-socialist fell prey to Opus 94a (commissioned by David Oistrakh). But Shaw may be forgiven, since the original version failed to gain currency until well into the LP era.

Israel Nestyev, Prokofiev's biographer, termed Opus 94 "an effusion of pure lyricism following the stark images of the Seventh Sonata, the Second String Quartet and the Ballad of the Unknown Boy." Indeed, stark, but nothing that could ever be called Heavy Mental! Prokofiev's best works by far remain freshly "neoclassical," such as the First Symphony and the Flute Sonata. Yet all display a typical off-kilter lilt, to which his son once revealed the secret: Every composition was nearly complete, then his father went back and "Prokofievized" it. Therefore we have the characteristic (although stupefying) Russian ballets, the rollicking Fifth Symphony, the menacing Nevsky, and the various concerti as his most popular pieces—also those that sound most like him.

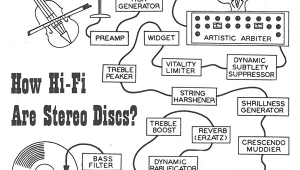

Thus it seems appropriate to discuss first the sonics presented here. Now "sound" as we hear it on a record involves many contributors beyond immediate control. For instance, the instrument-maker, the microphone-maker, the phonograph-maker. Final analysis cannot dismiss any of these, yet most reviews, including this one, do. Absolute polarity too displays its inimitable role, for no record may be heard aright without that vital adjustment. (Incidentally, this issue happens to be opposite those on the renowned Baker's Dozen Best list.) Whichever, we encounter (on gorgeously silent vinyl) a somewhat distant perspective on a rather nasty acoustic, the flute furthermore lacking focus (good tone, however) and the piano so remote, one wonders whether the two share the same stage. Turning to the reference recording (that aforehinted introductory LP, by Doriot Anthony Dwyer and Jesus Maria Sanroma, Boston 208—nla, alas), the flute, while somewhat fife-sounding, fairly leaps into the room, the piano striding firmly behind—a real team. Viva la mono!

As to performance, Woodward and Smith play the notes pretty well, although the former's constant vibrato serves no apparent expressive purpose. Dwyer, on the other hand, had me slapping my knee continuously at her felicitous turns of phrase. Pity, she retires this year from the Boston Symphony, where for decades she appeared to similar effect each week. Still, for consolation to the present artists (and engineer Kavi Alexander), Jean-Pierre Rampal's Erato account (on MHS) fizzles completely.

Overside, the Griffes Poem should alert everyone to an unduly neglected American master whose piano compositions especially merit greater attention. The Reinecke Sonata—well, perhaps we need Richter, who performed at the Prokofiev premier.

Does this initial release from the fledgling Stereophile label embrace the notorious J. Gordon Holt rule, the better the sound, the worse the performance? Definitely not! Here we have decent performances in decent sound.—Clark Johnsen, Boston, MA

Joint First-Prize Winner

I'll admit to some initial disappointment when, in the September 1989 issue, I read about Stereophile's recording of flute and piano works, performed by Gary Woodward and Brooks Smith. As was reportedly the case for Mozart, the flute is not one of my favorite orchestral instruments. I imagined 45 minutes of insipid 19th-century noodling and/or pseudoimpressionistic pap. Well, I need not have worried. Poem offers an involving musical program, solidly performed and stunningly recorded.

Gary Woodward's tone is quite beautiful—though broader, breathier, and less "gleaming" than Rampal's, less "high calorie" than Galway's. His lower range is absolutely sensual—Woodward manages to sound like an alto flute at times. He has ample technique and his intonation is never less than spot-on. Side one of STPH001-1 begins with Griffes's Poem, a dreamlike fantasy well suited to Woodward's romantic sound and sensibilities. The flutist's subtle tonal shadings of individual notes and phrases are marvelous, although the performance ultimately seemed a bit earthbound. The album's high point, for me, follows—the Reinecke "Undine" Sonata, one of this undervalued composer's better-known compositions. This beautifully crafted work, perfect in scale and form, is played by Woodward with an affecting simplicity and fluidity. Pianist Smith is very much at home with the Brahmsian piano idiom, and comes across as an equal participant.

Less successful is the Prokofiev D-major sonata. The performance seems cautious, especially Smith's contribution, which lacks incisiveness. Rampal (on Odyssey Y 33905), with his longtime partner Robert Veyron-Lacroix, gives a reading that is effortlessly virtuosic, with a real sense of abandon, especially in the exciting final movement.

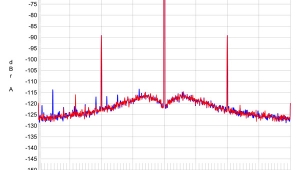

The sound is magnificent. The producers have certainly succeeded in their goal to preserve the true sound of acoustic instruments in a hall. Through my system—Grado TLZ, Premier FT3, VPI HW-19 II, ARC SP9 Mk.II preamp, Rowland Model 3 amplifiers, Mirage M-1 loudspeakers—the perspective is that of a seat in the front third of a small, empty hall. The piano is clearly close to the rear wall and the solo flute near the edge of the stage, well in front of the piano. Woodward's flute sound is amazingly consistent from top to bottom without any unnatural colorations, or a sense of strain when he plays loudly. The piano does sometimes lack focus and definition—the left hand in particular—but I suspect this is a response we all have after too many closely miked piano recordings. This is the way a piano sounds in a small, empty auditorium.

I compared Poem to the Wilson violin and piano discs that I admire greatly (Wilson W-8722 and W-8315). Although also recorded in a small hall, the feel is actually more like that of a living room—a perfectly valid way to make a "chamber music" recording. The sound is close and intimate. But I find Poem's sonics to be just as involving in the way they recreate the feeling of being in a real hall listening to real musicians. Kudos to Kavi Alexander and to Stereophile for producing a true reference recording. I eagerly await the next release.—Andrew Quint, Merion Station, PA

- Log in or register to post comments