| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Wow, JA! This could be the model for truly full reviews.Nice job.

So much for the effect of expectations on perception: the KX-R sounded better than no preamp at all! As Wes Phillips described in his review, music sounded especially alive through the KX-R, whereas with the Transporter driving the amplifiers directly, it was all a touch less involving; acoustic objects within the soundstage were all a tad less fleshed out.

But it could be argued that my finding should not have surprised me. Ever since reviewing Audio Research's groundbreaking SP-10 preamplifier in July 1984, I have suspected that the preamplifier is the heart of a system, that it colors and adds its own character to every signal that passes through it. What I hadn't anticipated was that this character might not be a mere absence of negatives, but could also be a positive attribute.

At $18,500, the Ayre KX-R was way too expensive for my budget, but since then I have reviewed more affordable preamplifiers: the Simaudio Moon Evolution P-8 ($16,000, September 2009), the Ayre K-5xeMP ($3500, June 2011), and, most recently, the Classé CP-800 ($5000, September 2012), which includes an excellent D/A section. The Simaudio P-8 came closest to the KX-R's ability to maximize musical communication, but at a cost that also came close, while the Ayre K-5xeMP undoubtedly offered the best balance of sound quality and price. But my quest continues. So when Pass Laboratories' affable PR man, Bryan Stanton, told me about the California company's XP-30 preamplifier ($16,500), I asked for a review sample.

Enter the XP-30

The XP-30 is unusual in that not only are the electrically "dirty" control circuitry and power supply housed in a separate chassis—a concept I first saw in the Mark Levinson No.32, from the turn of the century—it uses a separate chassis for each channel's audio circuitry. And although the sample sent me for review was a conventional two-channel model, the XP-30 can, with additional chassis, be expanded to as many as six channels. Each audio chassis has both a Master and a Slave output, duplicated on balanced XLRs and single-ended RCA jacks. The Master and Slave outputs each has its own output driver, and the balance between their levels can be adjusted with a rotary control on the front of the audio chassis. This allows the Slave output to be adjusted for use with a power amplifier having a different sensitivity from that used with the Master output—when, for example, a pair of speakers is to be biamped with heterogeneous amplifiers.

Each audio chassis has six analog inputs, duplicated on balanced XLRs and unbalanced RCAs. (When the latter are used, pin 3 of the corresponding XLR needs to be shorted to the pin 1 ground; gold-plated jumpers are provided.) Input 6 can be used either as a conventional input or as a Pass-Thru, unity-gain input for a Home-Theater Bypass. There are also a Tape Loop input and output, again duplicated on XLRs and RCAs. A Mono jack is used to connect the left and right chassis with a short cable fitted with same-sex XLRs, so that a proprietary blend of the two channels can be used rather the true L+R mono when Mono is selected with the front-panel button. The remote control has no Mono button, and its Power button works only with Pass Labs' integrated amplifiers. The preamps are designed to be on all the time—there is no off button.

The control chassis is the same size as the audio chassis, and contains a pair of low-noise Plitron transformers in a dual-mono topology, EMI filtering, and a large amount of reservoir capacitance. It is dominated by a blue fluorescent display on its front panel and a large volume knob to the display's right. Other than the Mono button, a recessed row of pushbuttons to the display's left is duplicated on the chunky metal remote control. A pair of DIN-25 multi-pin connectors on the rear of the control unit supplies power to each of the audio chassis. The umbilical cables supplied are long enough (6') to allow the audio chassis to be placed where convenient. The manual warns that these umbilicals need to be connected before the preamplifier is powered up. However, if you don't do so, as I did one time during my testing, no harm will come to the XP-30. The power supply has to see the gain channel through a loop-back-and-delay circuit before it will send power to the audio chassis.

Outside the XP-30

According to the manual, the XP-30 "is the result of several years' effort by Wayne Colburn and staff at Pass Labs and has undergone numerous designs, redesigns, revisions, more revisions, adjustments and tweaks; more than any preamp product with the possible exception of the XP-25 phono stage."

Wayne Colburn? Although many assume that Pass Labs founder Nelson Pass is the sole creator of everything that emerges from the Sacramento factory gates, a team of four is responsible. Pass Labs president Desmond Harrington, once a digital engineer, does all the industrial design. Joe Sammut is responsible for marketing and sales but also takes the leading role in auditioning prototypes and deciding when they are ready for the world outside. And as well as Nelson Pass, Wayne Colburn is responsible for creative engineering.

Colburn had worked with Pass at Threshold—he had answered an ad in Audio Amateur magazine for a "wizard's assistant"—and rejoined him at Pass Labs in 1994. I asked Colburn how he and Pass divide their responsibilities: "Nelson prefers to work on power amps, including laying out his own boards. I do preamps—the circuitry, the board layout, I write the software." Colburn was typically modest about his contribution to Pass Labs' engineering, but admitted that he was responsible for its integrated amplifiers. Desmond Harrington, recruited from Krell in 1996 to work on the mechanical engineering for the then-new X-series amplifiers as a "temple for Nelson's designs," told me that Pass is fond of saying, "The shark must go forward": the business must always advance, the designs must always improve, and to do that takes a team with diverse but complementary skills. It appears that Pass has no problem "gathering the talent," as Harrington put it, to enable Pass Labs to go where he wants it to go.

Inside the XP-30

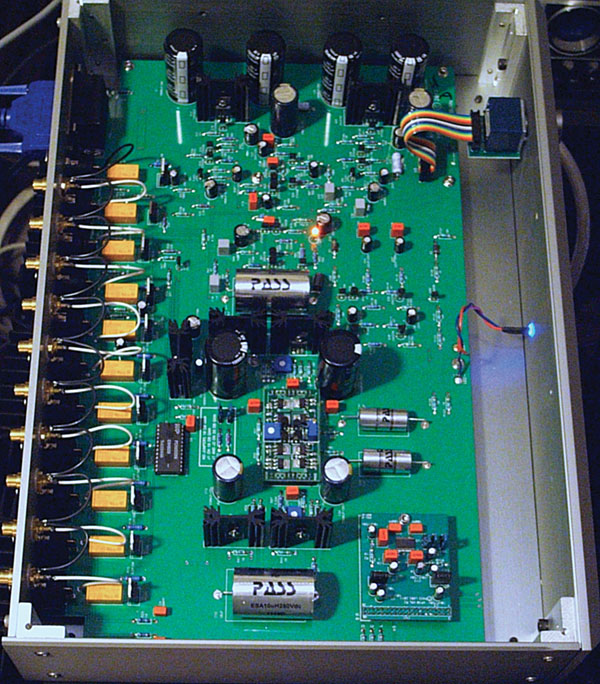

Each of the XP-30's audio chassis contains a single large, double-sided printed circuit board, with local three-pin voltage regulators and supply capacitance in abundance. Two large and two smaller caps, made by Clarity Caps and marked "Pass Labs," are presumably used for signal coupling. Input selection and switching are performed with high-quality relays, and a large, socketed CMOS chip handles the control housekeeping.

The input signal is fed first to the master balanced volume control, then to a symmetrical gain stage offering 10dB of voltage gain. This module, carried on a small daughterboard, is a more advanced version of the gain modules that have featured in Pass products since the 1990s. Claimed to have lower distortion and wider bandwidth than its predecessors, it also features a "dramatically" higher input impedance. The active devices are matched pairs of now-discontinued Toshiba JFETs and MOSFETs; however, Pass Labs says it has purchased enough of these parts to support production of the new gain stage for the next 10 years.

The gain module feeds the Master balanced output, a balanced–unbalanced summing amplifier that in turn feeds the single-ended Master output, and a pair of preset level potentiometers for the Slave output. These are followed by a unity-gain buffer to feed the balanced Slave output, and another balanced–unbalanced summer to feed the single-ended Slave output.

Echoing what Bill B wrote- This is a most excellent review.

Being fairly good friends with Wayne, I found your characterization of him to be spot on. He is as humble and down to earth as it gets and you couldn't meet a nicer person.

I'm delighted to see his human qualities recognized and represented so eloquently. When he told me he got this cover, I asked him how many print copies he was getting and he humbly shrugged it off as only he can.

Now I'll have to see about organizing a personal demo of the XP-30

Great review of a really well engineered product.

As the happy owner of both an XP-10 as well as an XP-20 I must admit music seems to be more involving and enjoyable since I've got them in my systems. Maybe it's the Pass Labs house sound or maybe it's simply the passion that their designers put in making those products.

Pass Labs products always seem to have soul...

With all due respect: Why on earth would anybody put a capacitor in the signal path. What if one has an amplifier with a low impedance input. The 600 ohms graph looks very much like the high pass filter of my speakers. Not in the XP-10, not in the XP-20 and not even in the Xs. What is goin' on in the XP-30...?