| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

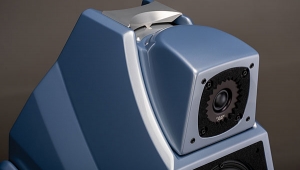

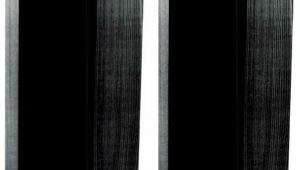

NHT 3.3 loudspeaker Greenberg 1994

Corey Greenberg wrote about the NHT 3.3 in March 1994 (Vol.17 No.3):

Footnote 1: This is somewhat too broad of a generalization. In three of the rooms I listen in regularly—the Stereophile room, Robert Harley's room, and my own—MLSSA measurements reveal the direct sound to be stronger or as strong as the reflected, without the listener having to sit particularly close to the speakers. Only in Larry Archibald's large room does the reflected sound dominate, which is why LA arranges to sit closer to the nearfield for critical listening.—John Atkinson

In my 1993 WCES report last April, I reported that the most impressive product I'd heard at the Show was the introduction of NHT's new flagship loudspeaker, the $4000/pair Model 3.3. Even under the iffy conditions of a show demo, the big 3.3s just floored me—I had honestly never heard speakers do what I was hearing these new NHTs do. Although the 3.3s had already been snatched up by Tom Norton for review, I made arrangements to get a pair into my He-Man listening room as soon as my plane touched back down in TX.

By the time TJN's review was published in December, I'd lived with the big NHTs for almost a year, so it was with great interest that I read his account of the speakers. Tom "got" many of the performance aspects which make the 3.3 such an outstanding speaker, but after living with the speaker for so long and comparing it to some of the best speakers on the market, I thought I'd offer my own impressions. Because, over a year later, I still marvel every time I sit down to listen to them—the 3.3s are, quite clearly, the best speakers I have ever heard.

When it comes to speakers, I am extraordinarily picky. I have ideas about what a high-fidelity speaker should do and not do that don't seem to jibe too well with most of the speaker designers flogging their wares in the High End. What I want, above all else, is accuracy. Not "accuracy" as in "it makes my recordings sound like a real concert," but rather the paradigm of perfect fidelity to the input signal fed the speaker's input terminals with regards to frequency response, time-domain response, distortion, and predicted soundfield based upon the recording technique employed in the making of the recording. Both as a professional audio reviewer in need of a reference listening tool and as a music lover who desires something which will pass on recorded music as faithfully as possible to the recording, not to my own idea of what the live event might have sounded like, I've craved such a speaker ever since I discovered that some audio gear sounds better than others.

I've gotten closer to this paradigm with each speaker upgrade I've made in the past several years, from Spica TC-50s to Spica Angeluses to ProAc Response 2s used with the Muse Model 18 subwoofer. Along the way I've listened at great length and become familiar with nearly all the contenders offered in the High End—from Alón to Wilson—but nothing I've heard has struck me as being as much of a harbinger of the future of loudspeaker design as the NHT 3.3.

With the 3.3, I hear a whole world of detail and spatial information in familiar recordings which I had never been even vaguely aware of with other high-end speakers. The big NHT is the only speaker I've heard that can essentially match the resolution of a pair of Grado headphones driven by the Melos SHA-1 headphone amplifier—my Ultimate Resolution Rig. For example, in "Rape Me" on Nirvana's In Utero, Steve Albini's excellent and fairly off-the-cuff recording includes a fair amount of studio chatter and other room noise buried beneath Kurt Cobain's vocal at the beginning of the tune. In addition, listening with the Grados/Melos reveals the vocal track to reside mainly in the left channel, although most speakers on which I've heard this track played interact sufficiently with the room's own acoustics that the voice sounds centered.

The 3.3's radiation pattern was designed to be different from that of most other high-end speakers to date. All other speakers, from forward-firing models like the Wilson WATTs/Puppies to dipole speakers like Magnepan/Apogee/Quad panel jobs and bipolar dynamic systems like the various Mirage and Definitive Technology speakers, have a very high ratio of reflected to direct sound when the speakers—and the listener—are located optimally in a room to minimize room modes in the bass range (footnote 1). This means that with any of these speakers, the listener hears as much or more sound that's been reflected off the walls, ceiling, and floor before it reaches his ears than he does direct sound from the speaker itself. And this is with a best-case setup. With the typical listening setup featuring speakers close to the wall behind them and the listener a good ways away on the other side of the room, nearly all the sound the listener hears is reflected sound that's bounced off one or more room surfaces before reaching his ears. Does that sound like a perfect window on the recording to you?

The 3.3 achieves a higher ratio of direct to reflected sound with two design features: the front panels are angled-in 21 degrees toward the listener to reduce the intensity of sidewall reflections that screw up imaging, soundstaging, and overall resolution; and there's a strip of thick open-cell foam mounted to the cabinet face just to the outside edge of the midrange and tweeter drivers, to further reduce their radiation off-axis toward the sidewalls.

To be sure, it's possible to approximate this aspect of the 3.3's design with many conventional direct-firing speakers. Positioning them well away from the rear and side walls, as well as toeing them in toward the listening position, will do much to increase their ratio of direct to reflected sound, especially if you also sit close enough to the speakers that you move out of the far-field, where the reverberant field predominates, and listen in the near-field, where you will hear, and I mean really hear, your speakers at their best.

But even so, this doesn't solve all the problems. Because once you set your speaker up in this manner, you'll probably find that, while the sound they produce is markedly more detailed and spatially focused, their bass range is now much less neutral than it was before you moved everything. The NHT 3.3 avoids this problem because it was designed to be located with its rear end right up against the wall behind it, in order to create optimal loading for its side-firing subwoofers.

So basically, with every other speaker, you have to choose between accurate bass and accurate everything else—with the NHT 3.3, you get both, and you get it no matter what kind of room you happen to have. Ken Kantor tried his damndest to get me to grok this aspect of the 3.3's design, but it only sank in after I spent seven dog-years mulling it over in my 8-Track mind. With every other speaker I've ever lived with, the entire room played a big role in determining the speaker's overall sound—that's why it took days to find the optimum position for all these speakers, with little nudges an inch here and an inch there going on for weeks, sometimes months afterward. By virtue of its design and much clever rethinking of the room/speaker interface, the 3.3 basically renders much of the room inconsequential in terms of affecting its sound.

Tied into this is a design feature NHT calls "Optimal Wave Loading": The amount of speaker diaphragm area each frequency range "sees" around it is optimized to minimize diffraction while maximizing even reinforcement. With the 3.3s against the rear wall and describing an equilateral triangle with the listening position, they will largely attain exactly the same level of accuracy as I've got right now in my own He-Man listening room. Unless your room is so narrow that your sidewalls are within a few feet of the speakers, or it's so small that you have to sit against or close to the wall behind you, the 3.3 reduces your room's contribution to the sound you hear—and once you hear your favorite recordings so utterly clear and free of detail-obscuring additive room effects, as I did with these NHTs, any other speaker in any other room will sound muddled and confused by comparison. Unlike most high-end speakers, which give the impression of detail by tipping-up the treble range, the 3.3 achieves its high resolution of detail by minimizing the kinds of room/speaker interactions that normally obscure low-level detail.

Soundstaging: One area in which TJN found the NHTs lacking with the occasional recording was their soundstaging. Even Ken Kantor admits that, with some recordings, the 3.3s can sound like headphones—closed-in, confined between the speakers, and not very open or spacious. TJN also noted that the 3.3s didn't seem to present images to the outside of the speakers, as some other speakers can do with some recordings.

All of this is true. I noticed a much greater difference in soundstaging and "outside imaging" between different recordings when played over the NHTs than I did with other speakers I had on hand or have used in the past. But what I found was that while some recordings did sound closed-in, as they did over headphones, others sounded so much larger and more realistically rendered over the 3.3s that I was stunned. Purist-miked recordings designed to preserve the natural recorded acoustic—like the Ry Cooder/V.M. Bhatt A Meeting by the River Water Lily Acoustics CD—were absolutely startling in their realism of reproduction when played via the 3.3. I heard layers of spatial detail I didn't hear even with the terrific ProAc Response 2s. I was able to close my eyes and "see" the entire layout of the chapel in which the recording took place with much more precision and ease than ever before.

Unlike TJN, I did hear plenty of beyond-the-speaker imaging with the 3.3s, but only when the recording actually featured this kind of effect. The Roger Waters QSound-soaked Amused to Death went way beyond the 3.3s, extending much wider than the Spicas and ProAcs had been able to in the same system. The 3.3s also had far greater focus of these "outside" images—the way-right piano on "Perfect Sense, Part I," for example, sounded just as focused and dimensional as any of the images between the speakers.

The NHTs had the ability to unravel complex phase relationships that determined spatial placement in recordings that were purposefully produced to achieve this kind of effect. One recording I've listened to at least a thousand times before revealed itself to possess a wild phase effect which I had never once heard on this track before. The intro to Jimi Hendrix's classic Electric Ladyland is a short snippet of sound-painting called "...And the Gods Made Love"—basically 1:21 of Jimi and producer/engineer Eddie Kramer trying to produce the sounds of the Almighty gettin' it on with His lovely lady with the use of Echoplex tape loops, overdriven guitar noise, and some extremely prescient use of out-of-phase information to put some of the sounds not only all across the soundstage, but inside your head as well!

That's right—the sound begins swirling as it builds into a ball of flanged hissing that then comes right up to you and enters your head, where it sounds as if it's recombining your DNA before exiting toward the speakerline and dying off as the track fades into "Have You Ever Been (To Electric Ladyland)." In the roughly 1000 times I'd listened to this track before I got the 3.3s, I'd never heard the swirling flanged hissing travel up to my face, enter my head, swirl around inside it for a few moments, then exit. I mean, I never even heard a hint of this effect before the NHTs, and let me tell you—there is nothing as startling in this entire pursuit than casually listening to a totally familiar record and hearing the sound travel toward the listening seat and literally enter into your skull. Nothing.

The bad news: That's the good news. The bad news is that many—no, I'll say most—recordings, be they LP, CD, or 8-Track, did sound confined to the space between the speakers, sounding smaller and less open than they do with conventional speakers. Whereas with these other speakers the sound would always be at least biggish and sometimes huge, the NHTs rendered recordings all the way from very small to insanely, unfetteredly gigantic.

This tells me that, rather than making all recordings sound larger than life due to the soundstage-enhancing effects of room reflections and the reverberant field, the NHTs present recordings in a much more accurate manner—and if the recording is small, it's going to sound small, and that's all you can ask a high-fidelity speaker to do. Maybe this is a hard concept to swallow, but you really have to hear these speakers to understand the implications, because the implications are that speakers which always present a large soundstage with every recording are inaccurate; that speakers which don't sound small when you feed them a small-sounding recording are inaccurate; and maybe, just maybe, everything you think you know about what an accurate loudspeaker sounds like is wrong.

Bottom line: Sad but true, most recordings don't have big soundstages. If you've been unknowingly compensating for this by using speakers that fudge the size of the image up so that most recordings sound more like what you would like them to sound like, you'll probably need some time to adjust to how most of your recordings sound via the 3.3s. But once you start hearing recordings for what they really are, your appreciation of those recordings which do offer a large and realistic soundstage, both purist and not-so, will greatly increase once you're able to hear the difference between real soundstaging and the room/speaker fish-eye lens thang. When I insert a piece of gear into my rig and the overall sound is far less "samey" on a wide variety of recordings, I know that I'm hearing a more neutral component than what I was using before it—and that's what I hear with the 3.3s.

Ah lahks mah rock'n'roll: Finally, the area which means the most to me personally: If you've been following my reviews these past few years, you know that Ah lahks rock'n'roll. And you also know that Ah lahks mah rock'n'roll loud, which is how rock'n'roll sounds when you hear it live. Now, there have been speakers available since the late '50s that could give you loud—the various Altec professional horn systems, Cerwin-Vega industrial beaters, Infinity IRSes, JBLs, and the fabled Klipsches from Hope, Arkansas, among others—but none could give you accurate. That is, clean loud. Linear loud. Loud that doesn't change the sound of the speakers at all from when they're not loud. Above all, loud that doesn't fatigue.

I learned my lesson with the Spicas. John Bau never claimed his speakers were for headbangers, but I loved what they did in the midrange so much that I bought both the TC-50s and later the Angeluses anyway—and dozens of blown woofs'n'tweets later, I finally had to accept the fact that, while I loved these speakers under 95dB, I needed that extra 30dB like I needed to breathe air into my lungs. Adding the mighty Muse subwoofer did much to extend the Spicas' dynamic range—replacing the Spicas with the ProAc Response 2s topped it off even further. But still there was a clearly discernible ceiling of operation above which things got pretty wiry—and that ceiling was quite a bit lower than I needed.

Now that I have the 3.3s, I have a pair of speakers in my listening room which can play louder than I can stand, while remaining clean, clear, and as uncongested as if they were whispering along at 80dB. Yes, you read that right—driven by the 200W Aragon 4004 Mk.II muscle amp, the 3.3s are capable of playing louder in my 1800 cubic feet listening room than I can stand for very long before I finally cede that I'd like to hear the word "Grandpa" someday and turn the volume down to a comfortable 110dB or so.

I just had never heard this kind of ability to play insanely loud while staying clean, clear, and unruffled in a high-end loudspeaker that can fit inside a Real World room. But the big NHT does it, and does it all day long without blowing drivers, your amp, or even its momentary cool. If you don't often listen to rock music, or any other kind of music at high levels, this aspect of the 3.3's performance will be meaningless to you. But if your listening diet is anything like mine, these speakers will be like manna from heaven to you. They rock!

NHT vs Thiel: Around the time I took delivery of the 3.3s, I welcomed a pair of the similarly priced $3900 Thiel CS3.6 loudspeakers (reviewed by Robert Harley in Vol.16 No.5), into my He-Man room for audition. Having been greatly impressed with the Thiels at CES, I was looking forward to hearing them in a more familiar environment to get to know them better.

Well, the Thiels certainly gave up some fine sound in my listening room, but I became aware of several potential drawbacks to their performance that ultimately ruled them out for me as long-term references. For starters, the 3.6 exhibited a pretty fat midbass that refused to flatten out no matter where I positioned the speakers and my listening chair in the room. While Robert Harley enjoyed the subjective "purring" effect this midbass fatness lent to electric bass lines, I found it to obscure bass detail, as well as serve as a constant reminder that I was listening to a fat-sounding loudspeaker instead of the illusion of a live performance.

But before I could even get to hearing this midbass fatness, I found soon after I'd unboxed the Thiels that none of the many amps I had on hand were able to drive the 3.6es to any kind of realistic levels with any kind of control in the bass. Worst match was the VTL Deluxe 225 tube amps (KT90 version), but even the solid-state Muse, Adcom, and Forté amps I had on hand couldn't do much better than the VTLs. Since I knew at the time that RH's review of the 3.6 was in the can but yet to be published, I called Stereophile to ask them why I was having so much trouble driving the Thiels. The answer was that the 3.6 presents a load not unlike a 2.5 ohm resistor across its entire range—one of the toughest and most demanding speaker loads currently on the market, and certainly one which only the most iron-fisted muscle amps can properly drive. True enough, it was only when I got ahold of the iron-aplenty Aragon 4004 Mk.II that I was able to really hear the Thiels at their best, the Aragon's large current reserves and ultra-low output impedance being ideal to deal with the Thiel's unreal load.

In many ways, the Thiel 3.6 typifies the best that current conventional high-end loudspeaker design has to offer—it was voted Stereophile's "Loudspeaker of 1993." Offering extremely good time-domain behavior due to the use of first-order crossover slopes and a slanted front baffle, as well as extremely pristine imaging and tonality (aside from the inescapable midbass hump), the Thiel can truly offer superlative sound when driven by one of the select group of high-current, low output impedance amplifiers capable of handling its demanding load.

But the NHT 3.3 is a whole 'nother world.

The Thiel can play just loud enough to almost reach minimum Rock-Approved levels before its midrange starts squawking and its passive-radiator-assisted woofer bottoms out—my ears gave out long before the NHTs even began to sound distressed, which I was only able to hear with foam earplugs stuck in my ears, and I'm not sure I wasn't actually hearing the 200W Aragon reaching its limits rather than the 3.3s reaching theirs. The Thiel's difficult load requires at least the likes of the $1850 Aragon, and, more appropriately, the likes of Krell and Mark Levinson. With its easier load, averaging between 4 and 6 ohms over most of the band, the NHT can be driven with just about any good-sounding amplifier, tube or solid-state, on the market.

The Thiels go down to around 30Hz and then abruptly drop off the map due to the radiator-assisted woofer loading. The sealed-box NHTs have a usable response to below 20Hz, and possess the deepest, tightest bass of any speaker I've ever heard. The Thiels present the kind of imaging and soundstaging I hear from many conventional high-end speakers; the NHTs tell me exactly what the recording actually sounds like. The Thiels are extremely fussy about room positioning; the NHTs go up against the wall behind them, you make sure they're exactly parallel with each other, and you're done.

The Thiels I listened to for a few weeks and then shipped back to the manufacturer; the NHTs I've been using as my reference speakers for well on a year now. To my ears, there was just no contest.

Shameless fawn-jizz time: To sum up what began as a short Follow-Up but got longer as I kept coming up with things I really dig about this speaker, the NHT 3.3 is the one for me. It does everything I want a He-Man reference loudspeaker to do, and, a year later, I find myself without a single area of performance I've heard bettered by any other speaker. While the 3.3 is sufficiently without character to well serve any kind of music fed it, I do believe that rock-loving audiophiles should consider the 3.3 the best-equipped on the market to deal with the special requirements of our chosen tuneage.

I don't consider many high-end products worthy of this kind o' shameless fawn-jizz, but the 3.3 is just plain the most impressive high-end speaker I've ever heard at any price.—Corey Greenberg

Footnote 1: This is somewhat too broad of a generalization. In three of the rooms I listen in regularly—the Stereophile room, Robert Harley's room, and my own—MLSSA measurements reveal the direct sound to be stronger or as strong as the reflected, without the listener having to sit particularly close to the speakers. Only in Larry Archibald's large room does the reflected sound dominate, which is why LA arranges to sit closer to the nearfield for critical listening.—John Atkinson

- Log in or register to post comments