| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

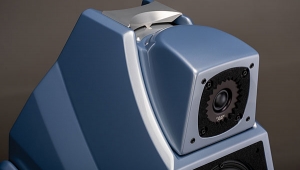

Merlin Excalibur II loudspeaker Page 2

Bass definition could have been better, especially from positions other than the primary listening spot. The only reason I heard this effect was because I spent a reasonable amount of time listening off-axis. The speaker was otherwise a fine performer from multiple listening positions. The Excalibur II is not a head-in-a-vise design. I was unsure of the source of the bass shortcomings off-axis because I could not rule out the amps I was using (Jadis Defy-7s), or my room (which remains problematic below 65Hz despite all my efforts to improve things).

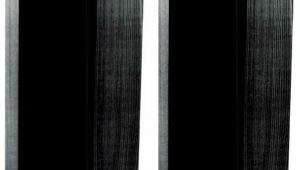

During the break-in period, I listened extensively to both analog and digital front-ends. The more I listened, the more I recognized the Excalibur's substantial improvements over earlier Merlin designs. The Excaliburs came alive at lower volume levels than the Signature Fours, played extremely loudly without glare or hardness, and presented a wide, deep, and open soundstage. In virtually every regard, the Excaliburs are a refined and evolved design.

As the weeks rolled by, my perception of the Excaliburs developed along two separate paths. First was the musical path, and the pleasure I experienced in listening (more on that later). The second—the review path—led me to concentrate on an assessment of the parts that were to make up the whole. As expected, both strengths and weaknesses emerged. With its high sensitivity and moderate impedance, the Merlins consistently sounded effortless, powerful, and dynamic. A wonderful example was the "Dragnet" track from Art of Noise's In No Sense? Nonsense! LP (Chrysalis OV 41570). This popular dance-club mix needs to be played loud, but many audiophile speakers unfortunately lack the requisite bottom end, dynamic range, and ability to play both loudly and cleanly. The Excaliburs, however, were very much at home with this type of music.

The Merlins' dynamic, effortless power was apparent with six different amps ranging in output power from 30W to 200W—the speakers were clearly an easy load. More important, there was no change in any aspect of their character when played at louder levels. They didn't get hard, produce grain or glare, or get muddled or confused. They simply performed as big speakers should. On many occasions I drove them to 100–105dB peaks with no sign of strain. At these levels, large-scale orchestral works and a great deal of rock were simply exhilarating.

Their soundstage furthered the Excaliburs' sense of "bigness." In my listening room, I was able to move the speakers 8' apart (from center to center) while still maintaining a focused image at center stage. The stage was presented behind and around the back of the speakers, affording a mid-hall seat. Depth was also effectively portrayed, especially at center stage. These soundstaging strengths allowed the speakers to differentiate the original spaces of each recording, from locations as diverse as David Manley's oft-praised studio (eg, Josh Sklair's Josh, VTL 013) to cavernous halls and churches (eg, Michel Corette's "Grand Chorus with Thunder" from Gargoyles and Chimeras, Delos D/CD 3077).

Depth was somewhat foreshortened toward the outer edges of the stage, with sounds occasionally collapsing toward or into the cabinets. This effect occurred more frequently on multitracked popular efforts such as the 4 Non Blondes' "What's Up" (from Bigger, Better, Faster, More!, Interscope 92122-2). With meticulous care in setup, the big Merlins had the ability to lock-in a precisely defined, rock-steady, three-dimensional set of images. An interesting illustration was Roger Waters's Amused to Death (Columbia CK 53196, SBM version). While many of the all-over-the-room QSound effects could be heard off-axis, the spatial wonder of this recording was particularly enthralling from the primary listening position.

The Excaliburs located the soundstage just above eye level, which was consistent with the acoustic centers of the vertical in-line driver arrays. As promised by Merlin, sounds from the different drivers at different frequencies were vertically centrally located within a broad horizontal plane, the speakers producing a frequency-related locational coherency. Unlike some speakers, the bass didn't come from somewhere near the floor while treble information was located at or near the tops of the boxes.

Speaking of boxes, the Excaliburs were remarkably free of box-like, or closed-in, colorations. One of their most arresting characteristics was an overall openness (eg, the Sklair or Peer recordings), with air around individual instruments and a re-creation of the recording space itself.

Of course, the most critical area of performance is always the midrange, the domain of the human voice. In this area, the speakers were first-rate—smooth, warm, and full. Harmonic structures were natural from sources as diverse as Chris Isaak's haunting solo voice (San Francisco Days, Reprise 45116-1, LP) or the full bloom of the London Symphony Orchestra (Rimsky-Korsakov's Capriccio espagnol, Telarc CD-80208). One of the keys to the Merlin's midrange magic was the way the speaker blended the upper bass and lower trebles into the midrange. Throughout this broad range, the character of the speaker was cut from the same cloth. As a pianist moved from the center of the keyboard in either direction, the sound clearly came from the same piano without changing its fundamental character. The broadened midrange was particularly satisfying with the full tonal splendor of an orchestra such as the Royal Philharmonic (Berlioz, Symphonie Fantastique, Chesky CR1). This surprised me somewhat, given the 500Hz crossover point between the lower-midrange units and the woofers. A second key to the midrange performance was the total absence of any additive coloration. There was no grain, glare, harshness, sibilance, or other non-musical intrusion.

Paradoxical parts

While the sound from the Excaliburs was consistently open and spacious, it was also somewhat of a paradox. After prolonged listening, I felt that the uppermost trebles were softened and mildly attenuated. Sounds such as the triangle on Rachmaninoff's Vocalise (Athena ALSW 10001), or the wealth of high-frequency information on Andreas Vollenweider's Caverna Magica (CBS MK 37827), were less obvious.

Since the speakers had level controls for the mids and highs, I wanted to turn up the tweeters' outputs. Unfortunately, this wasn't possible—the level controls for the tweeters can only be turned down relative to what is stated to be a flat position.

- Log in or register to post comments