| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

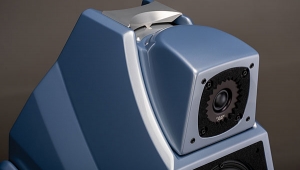

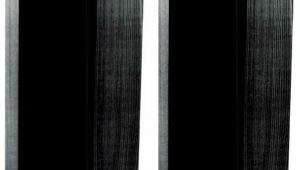

MartinLogan Prodigy loudspeaker Page 3

At these levels, the Prodigy's bass response sounded detailed and taut, and showed the advantages of the ForceForward design. Solid, clean bass extended down to 31.5Hz in my room when playing a 1/3-octave warble tone at -20dB (Test CD, Stereophile STPH 002-2). The bass drum in Owen Reed's La Fiesta Mexicana was tuneful, solid, and powerful (Fiesta, Reference Recordings RR-38CD). The final organ chords of Part 1 of Elgar's The Dream of Gerontius (Test CD 2, Stereophile STPH 004-2) and the repetitive bass-drum beat in "Cosmos Old Friend," from the Sneakers soundtrack (Columbia CK 53146), were clean, but I had to listen carefully because their reproduction via the Prodigys was subtle. Similarly, Michael Arnopol's plucked double bass on Patricia Barber's "Use Me," from Companion (Premonition/Blue Note 5-22963-2), pulsed, throbbed, and burned with no sign of bloat.

Footnote 3: Other critics have crowed about the Prodigy's dynamic range. See Myles Astor's review in Ultimate Audio (Winter 2001, Vol.4 No.4, pp.60-64), in which he praised the Prodigy's "ability to reproduce the speed and reduce the smearing of plucked instruments." UA named the Prodigy its Audio Product of the Year. In the December 2000 Home Theater (pp.113-120), Jerry Kindela lauded the Prodigy for its "marriage of micro- and macrosounds."

The Prodigy's bass had excellent pitch definition, the woofer's sonic characteristics to mesh well with those of the electrostatic panels. It captured the pounding tom-toms on Richard Thompson's "I Misunderstood," from Rumor and Sigh (Capitol CDP 7 95713 2); and the 32Hz bass notes from the beginning of Strauss's Also sprach Zarathustra, from "Ascent" on Time Warp (Telarc CD-80106), were clean and tight.

The Prodigy's midrange was transparent, timbrally accurate, and free of congestion and distortion. Vocal/clarinet/piano selections came alive as the speakers created a wide, seamless soundstage that gave no clue of their positions in the room. Vocals were reproduced with a transparency I'd missed ever since I'd let the Quad ESL-57s escape from my listening room. Suzanne Vega's startling a cappella vocal on "Tom's Diner" (Solitude Standing, A&M CD 5136) floated in the room with a lifelike fullness. The tonality of the saxophone and guitar were startling on the title track of the L.A. Four's Going Home (Ai Music Co. 3 2JD-10043). The same rich but totally natural timbre was heard in Buddy Miller's mando-guitar accompaniment to Emmylou Harris's "Prayer in Open D" on Spyboy (Eminent EM-25001-2). The guitar work on that track was crystalline and airy, with silken tonality.

The female voice was rendered faithfully, with natural timbre and low distortion. Patti Austin's rendition of Armando Manzanero's "Only You" (Hothouse, N2K 10023) was etched and holographic. Kim Cattrall reading "Little Dog's Day" sounded see-through clear and bell-like on Mark Levinson's Live Recordings at Red Rose Music, Volume 1 (Red Rose Music RRM 1). And I was transfixed by the a cappella choral blend on "Calling My Children Home," from Spyboy. Emmylou Harris's voice was effortless, ethereal, clear, and translucent.

Male vocalists fared just as well, with no midrange anomalies, suckouts, or other colorations. Willie Nelson sounded clear, clean, and totally free of honk or hollowness on "Getting Over You" and "Don't Give Up," from Across the Borderline (Columbia CK 52752). Harry Connick, Jr.'s tenor on "Don't Get Around Much Anymore," from the When Harry Met Sally... soundtrack (Columbia CK 45319), had none of the darkness and over-richness I routinely hear from dynamic speaker systems.

The Prodigy's treble spectrum was smooth and beguiling, with no brightness, steeliness, or metallic edge. Bells heard over this speaker had a magical sheen—as on Dvorák's Carnival, from Nature's Realm (Water Lily Acoustics WLA-WS-66-CD). The Japanese and Korean temple bells that back up Shane Cattrall's reading of Psalm 23 on Live Recordings at Red Rose Music were reproduced with stunning realism, transparency, and detail.

The Prodigys were able to maintain image stability at high volumes. On Going Home, the L.A. Four was precisely positioned on a wide soundstage, playing duets and solos on guitar, double bass, drums, flute, and saxophone. Images snapped into focus on the Prodigys' wide, well-defined sweet spot, whether José Carreras' holographic tenor singing the opening Kyrie of the Misa Criolla (Philips 420 955-2), or Richard Thompson's guitar as heard just outside the right speaker in the instrumental close of "Why Must I Plead," from Rumor and Sigh.

The sharpest and most precise imaging was heard from Sacred Feast, Sony's multichannel Super Audio CD recording of the choral group Gaudeamus (Sony SACD-9). Using a new Sony SCD-C555ES carousel SACD player, I selected a multichannel playback mode that fed full-range signals to the two front loudspeakers with no center channel. The result was a pure, airy, well-defined chorus rich in natural timbres.

Of all the Prodigy's sonic characteristics, the most impressive was its dynamic range. In my large listening room, it was one of the few loudspeakers that did not limit and crunch on the choral peaks of Elgar's Dream of Gerontius. Playing Spyboy's apocalyptic "Deeper Well" at top volume, I could still follow Emmylou Harris's birdlike voice and hear her lyrics clearly, despite the throbbing, churning bass synthesizer and distorted electric guitar.

The Prodigy handled both ends of the dynamic range beautifully, but just to be sure, I decided to push it hard. (footnote 3 I reconnected the Bryston 7B-STs and cranked up the volume until the amps' clipping lights flashed when playing snare-drum rimshots. In this configuration, the Prodigy bettered all loudspeakers heard in my living room. Not only did it reproduce the powerful wall of synthesizer and electric guitar and the explosive rimshots in the drum solo on "The Maker," the showstopper from Emmylou Harris's Spyboy, but it conveyed inner detail that most speakers miss. I heard a transparent, multi-layered aural portrait: a wall-to-wall tapestry of voices, synthesizer, drums, guitar, and crowd noise; the distorted but musical electric guitar solo; Harris's delicate but strained voice; the layered effect of the male backup singers; and those explosive rimshots.

Another revelation came when I played my favorite jazz selection, "The Mooche" from the Jerome Harris Quintet's Rendezvous (Stereophile STPH013-2). The Prodigy reproduced—better than I'd ever heard them—the honky timbre of the saxophone, the blattiness of the trombone, and the luminous, shimmering, see-through clarity of Steve Nelson's vibraphone.

Conclusions

The MartinLogan Prodigy reaffirmed my passion for electrostatic loudspeakers. Sure, I was swayed by the usual electrostatic attributes—low distortion, timbral accuracy, and deep, wide soundstaging that took my breath away—but there was more.

The epiphany came after I'd living with the Prodigys for two months. I don't know why it took that long—perhaps the woofers needed the time to fully break in and reveal their full dynamic range and power-handling capabilities—but music I'd always loved then came alive in a brand-new way. Instrumental timbres and colors became much more vivid, intense, and startlingly realistic. The speakers' dynamic range expanded, allowing them to play louder, with greater depth, three-dimensionality, and detail.

For these reasons, I strongly recommend you audition a pair of well-broken-in Prodigys with your favorite source material. Crank up the volume and listen. I promise you—the MartinLogan Prodigy will be a revelation, and the best cure for electrostatophobia.

Footnote 3: Other critics have crowed about the Prodigy's dynamic range. See Myles Astor's review in Ultimate Audio (Winter 2001, Vol.4 No.4, pp.60-64), in which he praised the Prodigy's "ability to reproduce the speed and reduce the smearing of plucked instruments." UA named the Prodigy its Audio Product of the Year. In the December 2000 Home Theater (pp.113-120), Jerry Kindela lauded the Prodigy for its "marriage of micro- and macrosounds."

- Log in or register to post comments