| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

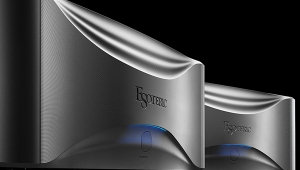

Krell KSA-50S power amplifier Page 2

Compared with the Stereophile-owned pair of Mark Levinson No.20.6es that reside in my listening room, the Krell '50S had a noticeably less extended, weighty bass. This is hardly surprising, considering the Levinson monoblocks have fully regulated output-stage power supplies and cost five times as much. What did surprise me was that the KSA-50S had a more liquid-sounding midrange. Eric Clapton's rather dead-sounding vocal on "Motherless Child," from From the Cradle (Reprise 45735-2), was more palpable, more solid. The difference was analogous to that between, say, Kodak Tri-X film and Ilford FP-4: the Levinson/Tri-X has a coarser grain structure but sounds/looks more dramatic; the Krell/FP-4 is less dramatic but has both a finer grain and a superior rendition of tonal dynamic range. With the KSA-50S, however, the B&Ws sounded more like the smallish speakers they really are.

Footnote 2: One comparison I had wished to do for this review was to hear how the $3300 KSA-50S sounded against the tubed Conrad-Johnson Premier Eleven A power amplifier ($3495) that Wes Phillips likes so much. (See his Follow-Up elsewhere in this issue.) Time constraints meant that this comparison was not possible; it will follow next month.—John Atkinson

Though the Krell sounded more polite than the Levinsons, this was not significant on well-recorded percussion-dominant tracks. "Waiting for the Buzz," for example, from Keith Terry & Crosspulse (Redwood RR 9401), mixes a steel-drum lead into a percussive soup consisting of congas, maracas/gourd, claves, and some kind of struck stringed instrument. Everything was audible via the KSA-50S, yet was neither exaggerated nor pushed unnaturally forward in the mix.

Image depth was also excellent. Jim Keltner's very natural-sounding drums on Clapton's From the Cradle CD (a nice engineering job on the band by Alan Douglas) were set well back in the image, with a good sense of space around them. And the intro to Andreas Vollenweider's Behind the Gardens—Behind the Wall—Under the Tree... CD (CBS MK 37793) was as wide, deep, and enveloping as I have heard. All the little fetishistic sonic details—the different characters of the reverberation chambers used on the harp and the percussion instruments, the differences between the bird sounds—were all laid bare for inspection by the Krell's combination of transparency and midrange sweetness.

KSA-50S vs KSA-100S

When I auditioned the Krell KSA-100S before publishing Bob Deutsch's review last September, I found, as did RD, that the '100S had a slight lack of dynamic drive. I felt this primarily to be a function of the amplifier's having a rather lightweight bass register—something I found surprising in view of the reputation of Krell amplifiers for powerful low frequencies.

Listening again to the KSA-100S after an interval of several months, I was struck by the same signature. The extreme lows were not as visceral as I was expecting—particularly when compared with the much-more-expensive Levinson No.20.6es. In addition, while the '100S's upper bass bloomed satisfyingly, this was perhaps too much in absolute terms. The bass guitar on "She Just Wants to Dance," from Keb' Mo's superb eponymous debut album (Okeh/Epic EK 57863), sounded rather indistinct, even considering that the B&W Silver Signatures are themselves rather ripe in this region. The synth bass line on Us3's "It's Like That," with its intriguing harmonic turn at the top of the riff, sounded a little behind the beat, too boomy, with the '100S driving the Silver Signatures.

Through its balanced inputs, the '50S was 0.21dB less sensitive than the '100S. I therefore matched levels by always increasing the Levinson preamp's output by 0.2dB when the '50 was driving the B&Ws. In a direct comparison with the '100S, the '50S actually sounded sweeter in the midrange. The smaller Krell, for example, made Barbara Hendricks' voice sound more delicate, less forceful, as she navigated the tricky ornaments and graces in the solo soprano part in the "Et incarnatus est," from Mozart's unfinished C-Minor Mass (Peter Schreier, Dresden Staatskapelle, Philips 426 273-2). The bigger amp, however, had more of a sense of ambient bloom around the orchestra—perhaps due to its more expansive upper-bass balance.

The '50S did have a better sense of pace, however. The "fat potato" synth line in the Us3 track mentioned earlier boogied a bit better via the more lean-sounding '50S. However, the persistent hi-hat cymbal riff on this track sounded more like real cymbals via the more expensive amplifier. Other than in the areas noted, these two amplifiers are very close in their overall presentations.

KSA-50S vs KSA-50

The original KSA-50 has only unbalanced inputs, so for the comparisons I hooked it up with 10' lengths of unbalanced AudioTruth Lapis fitted with RCA jacks. The '50S was auditioned in balanced mode so I wouldn't have to plug and unplug RCA connections, with all the potential for blowing up speakers and amps that that entails—hey, I own the B&Ws and one of the amplifiers, okay? The balanced 'S was 3.8dB more sensitive than the unbalanced '50; again, levels were matched to well within 0.01dB at 1kHz.

Listening to the original '50, which I haven't fired up in almost six years, brought the memories flooding back. The soundstage was wicked big; the bass was wicked deep; the amp was wicked GOOD! In the "Christe Eleison," from the Mozart C-Minor Mass's "Kyrie," Barbara Hendricks soars to a glorious climax. The old Krell allowed me to hear her voice lighting up the surrounding acoustic in a delightfully unambiguous way. And in the opening of the "Kyrie," the pulse of the dotted rhythm pushed the pace along.

The new Krell was significantly better than its predecessor in one important way: that gloriously liquid quality I noted earlier made the earlier Krell sound a little "electronic" by comparison. Hendricks' voice acquired a rather phlegmy edge via the older amplifier; the '50S presented it with a significantly more natural character. The original KSA-50's high frequencies were also grainier compared with the KSA-50S, and slightly sibilant. The new amplifier had altogether a more civilized, more neutral sound, I found. But when it came to the soundstage, the Dresden walls weren't illuminated to the same extent as they had been with the old amp.

And the new amp lost something of the sense of pace. It wasn't that it couldn't boogie at all, but when it did so, it was definitely in a more mannered way. Despite the more natural, less grainy presentation of the vocal, the combination of bass guitar and kickdrum on "Tell Everybody I Know," from the killer Keb' Mo' album, for example, could officially be classified as "polite" through the '50S. Perhaps as Krell designer Dan D'Agostino and the rest of us baby boomers get older, so does the sonic character of Krell amplifiers keep pace with our shifting desires.

Conclusion

While the Krell KSA-50S's bass is not quite as awesomely kick-ass deep as the earlier KSA-50, its midrange is one of the best I have heard from a solid-state design. Its imaging and soundstaging are also both first-rate. The KSA-50S is one civilized-sounding amplifier. And perhaps that's also my only real criticism: that it has lost some of the slam, the "Wham, Bam, thank you, Dan!," that characterized the original KSA-50 (footnote 2).

The KSA-50S is undoubtedly a contender, but its sonic character makes it essential for you to audition it in the context of your own system. Recommended—but news we've just received from Krell could make this moot. Apparently the KSA-50S might be discontinued in September, due to lack of demand: Krell customers appear to be more prepared to spend the big bucks for the bigger amplifiers. Given the '50S's sweet sound and massive power delivery, I feel that this is a pity.

Footnote 2: One comparison I had wished to do for this review was to hear how the $3300 KSA-50S sounded against the tubed Conrad-Johnson Premier Eleven A power amplifier ($3495) that Wes Phillips likes so much. (See his Follow-Up elsewhere in this issue.) Time constraints meant that this comparison was not possible; it will follow next month.—John Atkinson

- Log in or register to post comments