| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

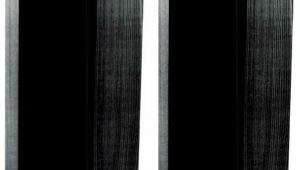

Focal-JMlab Grand Utopia loudspeaker Page 2

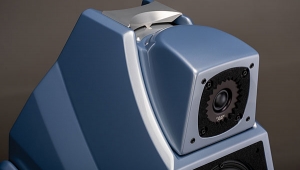

In most cases I prefer to aim speakers directly at the listening position; I find this often yields the optimum soundstaging dimensionality and image focus. Doing so with the Grand Utopias was the wrong decision: the treble balance suffered, but in a manner opposite to what often happens. In this case, the amount of high-end energy decreased when I was looking directly at the front face of the cabinets, no doubt because of the plates mounted on each tweeter. Optimal treble performance was best, as intended by JM, well off-axis—in this case, with the speakers aimed straight ahead.

My last set of early trials with the speakers concerned top-to-bottom coherence. Initially, I was unhappy with the noticeable phenomenon of multiple drivers (re)creating music. Moving my listening seat back a bit farther than normal proved to be the solution. At a certain distance, everything meshed together in a far more satisfying fashion.

One issue that I expected to be a problem turned out not to be one. At first, I assumed that: 1) I was shorter than the average expected Grand Utopia listener; 2) my listening chair was too close to the floor; or 3) the tweeters were too far from the floor. Once again, I assume JMlab didn't want my (or your) ears directly on the axis of the tweeter and its damping plate.

One of my biggest surprises occurred during setup. In my experience, most true high-end speakers are terrible at low levels. But as I effortlessly moved the Grand Utopias about, I continuously played music through them, and, no matter how low the volume, I enjoyed it. These huge monoliths were extremely adroit at playing softly. This may be related to their tonal balance and high sensitivity; they had body and life even at unrealistically low levels.

As nutty as it may seem, these monsters were superb for background music. Many visitors to my listening room were shocked at the delicacy these 800 lbs of loudspeakers were capable of. A great example was the ethereal voices from the Anonymous 4 (An English Ladymass, Harmonia Mundi HMU 907080). Non-audiophiles in particular seem to always expect a BIG sound out of big speakers, regardless of source material. Solo acoustic guitar, acappella voices, and wispy new age material consistently shocked visitors to my listening room.

Adding to its wonderful ability to sound delicate was the Utopia's emotional splendor in sounding beautiful. The caressingly sweet upper reaches of a violin were a constant case in point from both LP (eg, Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade, Chesky RC4) and CD (Midori, Live at Carnegie Hall, Sony Classical SK 46742). The Grand Utopia's upper limit was well above my own hearing capabilities in terms of quantity or output but, more important, it had a believable quality of fullness, detail, focus, speed, and everything else I forced myself to listen for.

This was harder than I expected. It was always the music I was actually listening to—it took a great deal of effort to pay any attention to the speaker. But when I did, I was captivated by appropriately splashy cymbal onslaughts (Dave Brubeck, Time Out, Classic/Columbia CS 8192), wailing top-of-the-neck guitar attacks (The Essential Jimi Hendrix, Vols.1 and 2, Reprise 26035), and staccato keyboard pyrotechnics (Nojima Plays Liszt, Reference RR-25). Once I paid attention to the treble performance, I could find no fault. Shortcomings came from source material and other equipment, not from the speaker itself. Though changes in speaker cables and amplifiers were immediately obvious in the top end, the speaker simply reproduced whatever it was fed—and feed it I did.

But it was the opposite end of the frequency spectrum that was the most initially arresting. The Grand Utopia's bass extension went on forever, rivaling that of any other speaker—including subwoofers—I've ever had in my listening room. But it didn't just dig deep, it did so with the same naturalness I heard in the treble: it was rich as well as simultaneously fast and detailed. Pumped up to real-world volumes, the bass lines on Ben Harper's Welcome to the Cruel World (Virgin 39320-2) jumped on my chest and grabbed me by the ears, shouting for attention. Michael Murray's attacks on the Cavaillé;-Coll organ at Saint Quen de Rouen made Vierne's Symphony 3 (Telarc CD-80329) shake the very foundation of my listening room, air thundering through the pipes in a controlled fury evocative of a hurricane or cyclone. In this case, big speakers made big bass! The bottom end was so strong my initial reaction to the Grand Utopias was a feeling that they were bass-heavy. Over time, I realized that they were nothing of the sort—it was just a problem of listening to home hi-fi. The overwhelming majority of speakers are bass-deficient. Only in comparison with any number of other speakers did the JMlabs sound bass-heavy. Compared to live music, they could really handle true low-frequency information.

But here the threads begin to weave together into the pattern of my ultimate evaluation of these speakers. Like other good big speakers, the Grand Utopia could reproduce great bass. Driven by a pair of Classé 1000s bridged for mono, they produced extraordinary bass. But unlike many other big speakers, the Grand Utopias didn't always sound big. They only sounded big when the music warranted it. Images were never larger than life unless they'd been recorded that way (eg, Johnny Hartman's Once in a Lifetime, BeeHive BH7012). Solo performers and delicate instruments were reproduced with the appropriate scale and level of accuracy, the same fine realism, as full orchestras and live rock concerts. The monstrous Grand Utopias handled Suzanne Vega (99.9°F, A&M 54001) with kid gloves, and gently unraveled the complex array of unusual sounds from Andreas Vollenweider's Eolian Minstrel (SBK/ERG 27897-2), sounding as petite and delicate as each respective source.

As I've mentioned, these speakers were surprisingly good at low volume levels and astounding at high levels. They were also terrific at getting everywhere in between. Given their high sensitivity, it was not much of a surprise that these beauties were sensationally dynamic, putting back the jump in reproduced music that is all too often missing. They simply had that magical ability to spring to life with the vibrancy of something real—as evidenced in the awesome street-smart bombast of Sergio Mendes's Brasileiro (Elektra 61315).

My little son and I samba'd all over the house, the speakers easily passing Bob Deutsch's Listening From Another Room Test. Heck, had the weather been better, we might have danced right out into the street, subjecting the JMlabs to the Listening From Outside The House At Unlawful Volumes Before Being Arrested Test. More critically, the Grand Utopias were excellent at re-creating all of the subtle micro volume levels of music. Ella Fitzgerald's "Cry Me A River" (Clap Hands, Here Comes Charlie!, Classic/Verve V6-4053) provided a lovingly natural example. But most important of all, they handled all of these levels and transitions in a totally effortless manner. One of my all-time favorite tests of this particular phenomenon is John Handy's Excursion in Blue (Quartet Q1005CD). It was captivating. It was music.

The combination of bass, dynamics, and overall sense of power made these the ideal choice for all sorts of music, including the always demanding organ. Oh, the splendor of John Eargle's recordings! (Sampled on Engineer's Choice, Delos DE 3506.) As I listened, I was struck by how much was being revealed in all these masterful organ works about where they had been recorded. The spaces themselves had weight and volume, a sense of heft rarely properly captured. Live recordings weren't simply spacious because they had a light, airy character. There were halls and rooms filled with ambient noise, decaying sounds, and reverberant fields. In contrast, many other speakers have sparkle but little body in portraying naturally occurring waves of sound in real space.

While the music never ceased to enthrall me, I was occasionally reminded of the presence of the speaker cabinets. Unlike the best minimonitors, the huge Grand Utopias never entirely disappeared into the soundstage. Oddly, this wasn't because sounds were clearly coming from the drivers, as they do with certain other speakers, it was the soundstage that was bounded, as opposed to the individual sounds being so directionally sourced. The cabinets themselves often defined edges or parts of the soundstage, with performers placed with well-focused precision between, behind, or within them. Width and depth were both good, and my hall seat was a bit back (which I prefer), though neither at the back nor the front of the hall.

For some small-scale performances, speakers with a closer perspective provide a more intimate relationship with the artists. Given the distance to the listening seat required to achieve proper overall coherence with the big JMlabs, I don't think this is a characteristic they would be are capable of achieving. But having said that, the Utopias were fully capable of precisely placing sounds all over my listening room when playing Roger Waters' QSound-mixed Amused to Death (Columbia CK 53196). I generally regard this as an indication of a product's overall phase performance; everything I heard led me to believe phase was still another attribute handled adroitly by these speakers.

As I tried to pay attention to the bevy of drivers, I became aware of still more audiophile traits that hadn't drawn my attention before. These babies were, as advertised, clean and fast. Transients sounded like transients, with clearly defined starts, stops, sustains, reverbs, and decays, as required. Once again, I was sucked in by the jump from the brass on the great direct-to-disc recording Sonic Fireworks, Vol.II (Crystal Clear CCS-7011), and was caught playing an armful of air-instruments along with Spyro Gyra (Catching the Sun, MCA 5108).

But as long as the JMlabs occupied center stage in my room, it was always the music I returned to. Lovingly, the harmonic richness of the bass and the sweet delicacy of the treble were both found in abundance where it mattered most—through the critical range of the human voice. I lolled in the textural palpability of Chris Rea's startling instrument as I journeyed with him on the "Road to Hell" (The Best of Chris Rea, East West 98382); reminisced with Richie Havens and his open-tuned acoustic guitar as we revisited the '60s (Collection, Rykodisc RCD 20036); marveled at the bell-like purity of Joan Baez (Vanguard VRS 9078); and got lost in the humanity of Laurie Anderson (United States Live, Warner Bros. 25192). The haunting splendor and vast complexity of the human voice were very much at home with the Grand Utopia, providing the luscious icing on the proverbial cake.

Stunning

The JMlab Grand Utopia is an absolutely stunning accomplishment in every regard. It was able to let music sound like music—at levels high, low, and everything in between. It was dynamic, detailed, fast, and—most critically—beautifully musical. Truly one of the world's greatest loudspeakers. (Now—where'd I put that lottery ticket...?)

- Log in or register to post comments