| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

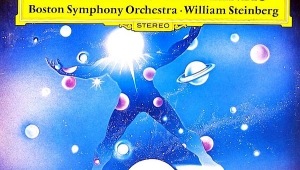

I can't begin to thank you enough for exposing me to Alex North's original score for 2001: A Space Odyssey! It is crystal clear from the very first few bars why Kubrick was so keen on the temporary public domain tracks. Knowing now what we could have been forced to endure really gives me that much more appreciation for those truly timeless classics from the past greats. North's work will always be a product of the 50's and early 60's: strident and cacaphonic, which was a perfect reflection of the world at that time---all well and good for his previous works, but completely wrong for the groundbreaking vision of the prophesized future of 2001. I think even more people would have hated the film than they did (and do) if it had been portrayed with North's...unique interpretations.