| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

The Fifth Element #73 Page 2

A prodigy who wrote his first oratorio at 11, famed film composer Nino Rota studied with Alfredo Casella at the Santa Cecilia Academy, in Rome. Toscanini encouraged Rota to come to America, where he won a scholarship to the Curtis Institute; his teachers there included Fritz Reiner. Rota's more than 150 film credits include Fellini's 81?2, Zeffirelli's Romeo and Juliet, and two of Francis Ford Coppola's Godfather films. I had been dimly aware that Rota had written "serious" music, but had never sought it out until prompted by a reader's entry. My mistake. Everything on this CD is excellent music, the playing is faultless, and the engineering enviable. The Cello Concerto 2 is more than a little reminiscent of that other successful film composer, Dmitri Shostakovich (as well as of Poulenc and Prokofiev). The neoclassical, slightly moody Concerto for Strings deserves its place as Rota's most popular "serious" work. The Poulenc-esque Trio for Clarinet, Cello, and Piano is a perfect little chamber-music gem.

Berwald: Symphonies 1–4, Overtures

Roy Goodman, Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra

Hyperion Dyad 22043 (2 CDs). 2004. Oliver Rivers, Andrew Keener, Jan B. Larsson, prods.; Tony Faulkner, Ian Cederholm, engs. DDD. TT: 2:25:21

Franz Berwald was born in Stockholm in 1796, one year before the birth of Franz Schubert. His father was a violinist in the orchestra of the Royal Opera, and Berwald developed into a child prodigy on the violin. For various reasons, recognition for his playing and his compositions eluded him, so he opened an orthopedic clinic in Berlin, which he ran successfully for several years; eventually, he returned to Sweden to run a sawmill. Berwald's music was little performed in his lifetime. There have been anniversary revivals in Sweden, but his music has been largely forgotten, except where it has remained totally unknown. That is a pity. His Symphony 3, "Singulière," of 1842, sounds like Mendelssohn being gently dragged in the direction of Carl Nielsen. It's easy to see why provincial audiences and conservative big-city critics would have been put off by its forward look, but you won't be. The set collects most of Berwald's extant orchestral scores in idiomatic performances and excellent sound, and is priced as a single CD.

Rott: Symphony in E

Leif Segerstam, Norrköping Symphony Orchestra

BIS 563 (CD). 1993. Robert von Bahr, prod.; Siegbert Ernst, eng. DDD. TT: 64:07

Poor Hans Rott brings to mind Oscar Wilde's quip that while to lose one parent may be regarded as a misfortune, to lose both looks like carelessness. When Rott was 14, his mother died. Two years later, his father, a comic actor, was crippled in a stage accident and died two years later. So Rott started at the Vienna Conservatory a penniless orphan-scholarship student. Anton Bruckner took Rott under his wing; Rott is reported to have been Bruckner's favorite organ student. However, the first movement of Rott's Symphony in E (1878–1880) did not fare well at the hands of Bruckner's faculty colleagues. It didn't even receive a grade in the annual compulsory composition competition.

Here is where things get very dicey. Rott and Gustav Mahler were classmates, and at one time had been roommates. Rott completed his first symphony four years before Mahler had even begun his own first symphony. Mahler praised Rott as "the founder of the new symphony as I know it," but by then Rott had died in an insane asylum. It was not until 1989—when Paul Banks, intrigued by Mahler's praise for an unknown, had prepared a performing edition of Rott's Symphony (recorded by Gerhard Samuel and an orchestra from the Cincinnati Conservatory)—that it became clear that Mahler had "borrowed" from Rott for his first two symphonies, and perhaps for his third as well. Whether the fairer judgment is "influence" or "plagiarism" remains a controversy among some contemporary musicologists. To quote the Starship Enterprise's Science Officer: "Fascinating."

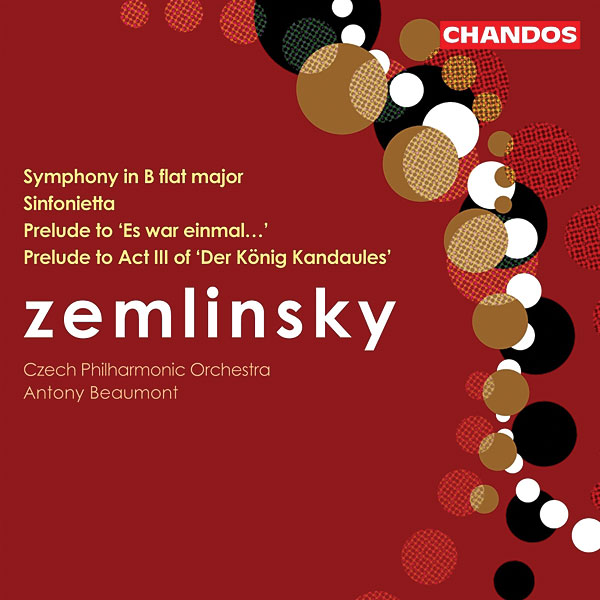

Zemlinsky: Symphony 2

With: Sinfonietta, Prelude to Act III of Der König Kandaules, Es War Einmal . . .

Antony Beaumont, Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

Chandos 10204 (CD). 2001/2004. Ralph Couzens, Dominic Fyfe, Milan Publicky, prods.; Oldrich Slezák, eng. DDD. TT: 76:00

I wonder whether Gustav Mahler ever came to wish that Alma Schindler had ended up marrying Alexander Zemlinsky rather than him. Alma had given up Zemlinsky for his lack of international prospects and his homely appearance. Another Bruckner student, Zemlinsky was an organist whose early music appealed to Brahms. Schoenberg married Zemlinsky's sister; thereafter, Zemlinsky gave Schoenberg counterpoint lessons, making Zemlinsky Schoenberg's only formal music teacher. Parts of the first movement might strike one as photocopied Dvo?ák (not a bad thing), except that there's an underlying sadness that Dvo?ák seldom tapped into. The second movement is a self-assured example of formal development. There are lovely moments in the third movement and blissful moments in the fourth—which includes, possibly as an homage to Brahms, a quasi-academic five-part fugue for strings. This compilation also includes the first recording of the original version of the Prelude to the opera Es War Einmal . . . , whose world premiere Mahler conducted. The Czech Philharmonic and Antony Beaumont are in top form.

Suk: Symphony 2, Asrael

Claus Peter Flor, Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra

BIS 1776 (SACD/CD). 2009. Jens Braun, prod.; Hans Kipfer, eng. DDD. TT: 60:18

Suk's Symphony in c of 1905–1906, subtitled Asrael for the Angel of Death in Islamic angelology, was occasioned by the death of Suk's father-in-law, Dvorák. But before Suk could complete it, Suk's wife, Otylka, also died. Expect a bumpy ride. The symphony is in two parts, encompassing five movements. While it may be apt (in some sense) to observe that the orchestration overall calls to mind that of Richard Strauss, that one section could be inspired by a Mahler funeral march, and another has echoes of Wagner's Tristan, all that disserves Suk's originality and craftsmanship. If you need to first dip in only a toe, the second of two slow movements, Adagio, has a lovely violin solo. In its complexity, length, and emotional intensity, this demanding recording is the polar opposite of the Puccini and Rota CDs, and Asrael is well worth getting to know. The sound is luminous, and the Malaysian Philharmonic plays like a world-class orchestra.

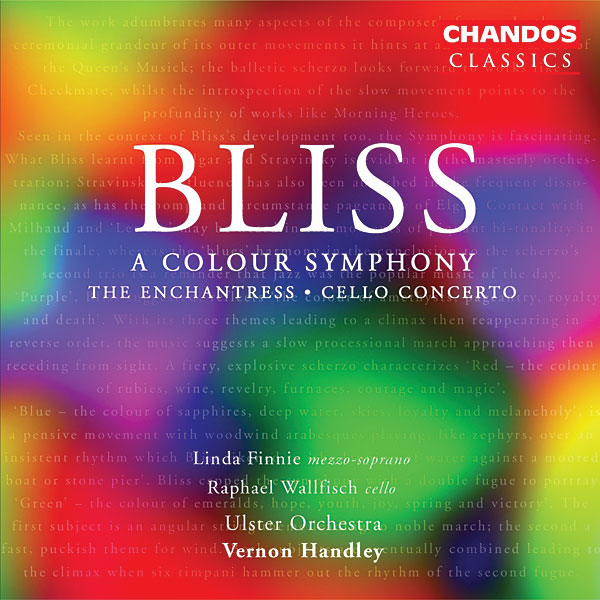

Bliss: A Colour Symphony, Cello Concerto, The Enchantress

Linda Finnie, mezzo-soprano; Raphael Wallfisch, cello; Ulster Orchestra, Vernon Handley

Chandos 10221 (CD). 1987/2004. Brian Couzens, prod.; Ralph Couzens, eng. DDD. TT: 75:44

The young Arthur Bliss received his first commission for a major work and promptly caught a very bad case of writer's block. Browsing the bookshelves at a friend's house, Bliss took down a volume about heraldry and, in reading about traditional heraldry's associations of colors with attributes (eg, "Red—the colour of rubies, wine, revelry, courage and magic"), found his inspiration. A Colour Symphony is inspired and hugely accessible. Imagine Elgar, but updated with a dash of Stravinsky's dissonance and a soupcon of self-confident Milhaudian cheek. If you've pigeonholed Bliss as a composer of film and ballet music, think again—this CD includes his late-period Cello Concerto and The Enchantress, a work formally similar to Barber's Knoxville: Summer of 1915.

Rautavaara: Symphony 8, The Journey; Violin Concerto

Jaakko Kuusisto, violin; Osmo Vänskä, Lahti Symphony Orchestra

BIS 1315 (CD). 2004. Robert Suff, prod.; Ingo Petry, eng. DDD. TT: 56:41

One might criticize Rautavaara's Symphony 8, composed in 1999, for its lack of traditional development and for being episodic, but in all fairness, do not those criticisms apply also to Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra? Rautavaara's writing is dissonant but not ugly; even when his music is foreboding, the scoring is warm and lush. The work was commissioned for the Philadelphia Orchestra, and Rautavaara kept in mind both that ensemble's celebrated tonal richness and, in the Bartókian scherzo, their virtuosity. A dense and challenging work, and rewarding to listen to. The Violin Concerto has echoes of Barber's and Bartók's works in that form.

Schreker: Orchestral Works

Prelude to a Grand Opera, Intermezzo for Strings, Prelude to Die Gezeichneten, Romantic Suite

James Conlon, Cologne Gürzenich Orchestra

EMI Classics Special Import 56784 (CD). 1999. Daniel Zalay, prod.; Hilmar Kerp, Hartwig Paulsen, engs. DDD. TT: 66:28

In 1914, Franz Schreker reworked the Prelude to his work in progress, the decadent opera Die Gezeichneten (The Stigmatized), into the standalone orchestral work Prelude to a Grand Opera. One would be tempted to yell "Copycat!" at Alexander Courage, who composed the theme music for the original Star Trek TV series, and perhaps at John Williams as well—but it's unlikely that either had even seen Schreker's name. After the opera's premiere in 1918, a succès de scandale, more than 60 performances followed in Europe. But in 1933 Schreker's works were banned by the Nazis. The opera was revived in 1979; four recordings are now available, but it was not performed in the US until 2010. Based on the works on this CD, Schreker was a master orchestrator and a highly individual composer—his sounds shimmer in space.

Adams: The Dharma at Big Sur, My Father Knew Charles Ives

Tracy Silverman, six-string electric violin; William Houghton, trumpet; BBC Symphony Orchestra, John Adams

Nonesuch 79857-2 (2 CDs). 2006. Martin Sauer, prod.; Tobias Lehmann, Mark Willsher, engs. DDD. TT: 53:00

This one pushed all my "bad" buttons. "Like, wow, man, you really have to check out the dharma you get up at Big Sur. It'll change your whole vibe." Then, when I saw that it was a concerto for six-string electric violin, all I could do was write a note to myself to bring it to my next aromatherapy session, for background music. However, it is often good to listen to things you're sure you won't like. The Dharma at Big Sur is a wonderful concerto, virtuosic and rich in content. Each of its two movements is a tribute to an American composer: the rather meditative first to composer Lou Harrison, the virtuosic second to Terry Riley. Over and above the predictably unusual gamelan-like orchestration, the work is interesting because it is written in just or pure (not equal-tempered) intonation, in the key of B—except for the second harp, which is justly-tuned in the key of E. As if that weren't enough, the six-string violin extends a fifth below the range of the viola, to F, which provides surprising bass. Soloist Tracy Silverman plays the pants off the violin part. The other Adams work here, My Father Knew Charles Ives, is also well worth getting to know. (Dharma shows signs of catching on; Leila Josefowicz and Adams recorded it with the Los Angeles Philharmonic in 2009 for Deutsche Grammophon. Good!)

Tredici: Final Alice

Barbara Hendricks, singer; Sir Georg Solti, Chicago Symphony

Decca Eloquence Australia 442 995-5 (CD). 1981/2008. James Mallinson, prod.; James Lock, John Dunkerly, Michael Mailes, engs. DDD. TT: 59:07

This work, dedicated to conductor Sir Georg Solti, might have pushed all my anti-trendoid "bad" buttons, except for the fact that, back in the day, I purchased and was charmed by a Nonesuch CD of In Memory of a Summer Day, another of the large-scale works in which Del Tredici obsesses over the relationship between the actual people in the background of Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass: Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) and 11-year-old Alice Pleasance Liddell (Alice). I didn't follow up and obtain Final Alice, a song cycle composed before Summer Day. I now regret that I did not—it's the stronger work.

The soprano (Barbara Hendricks) both narrates, by reciting from Wonderland's courtroom scene, and sings arias based on poems connected with the novel. The final aria, a setting of Carroll's acrostic poem "A Boat, 'Neath a Sunny Sky," is heartrendingly poignant. Del Tredici's writing, on the surface so much like a nursery song, has subtle and troubling depths. Final Alice ends with the oboe playing the A (440Hz) to which the rest of an orchestra tunes, making an evening featuring this work something of a musical palindrome. Leonard Slatkin has revived Final Alice with soprano Hila Plitmann, who is married to composer Eric Whitacre. All praise and honors to the Detroit Symphony for putting up an HD-quality YouTube video of Plitmann performing in concert this past March the final aria of Final Alice. Don't miss it! I can't wait for their new, uncut recording (Solti's omits two scenes), to be released early next year.

Shostakovich: An Introduction to Dmitri Shostakovich

Piano Concerto 2, Symphony 5, Festive Overture, Tahiti Trot

Neeme Järvi, I Musici de Montreal. Concerto: Dmitri Shostakovich Jr., piano; Maxim Shostakovich, Royal Scottish National Orchestra

Chandos Intro 2027 (CD). 2006. Rachel Smith, remastering. DDD. TT: 74:42

This budget compilation is a three-fer winner in our Fantasy Symphony Season write-in competition. Shostakovich's Symphony 5 was the second-most-popular work among the winning entries; his Piano Concerto 2 was included in my own season; and his quirky, charming orchestration of "Tea for Two"—written from memory, on a bet, in 45 minutes, after hearing a recording of the song once—made this list of Unfamiliar Treasures. Although in 1928 the USSR subscribed to no international copyright conventions, I assume that the Soviet authorities didn't want to rub Westerners' noses in blatant infringements. So by way of protective coloration, Shostakovich's orchestration of "Tea for Two" is titled Tahiti Trot. Who knew?

- Log in or register to post comments