| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

What decade are you living in?

Including a new ~$400 standalone CD player as part of an "entry level system", in comparison to other current options, would be a poor allocation of precious resources.

I would agree that Redbook compatible CD audio is far from obsolete, as there will be trade in used CDs long after the publishing of new releases has slowed to a trickle.

But the $400 wasted on that CD player is more than enough to buy a SqueezeBox Touch ($250), an inexpensive external USB HDD (under $100), and a powered USB hub (under $50). Extract digital audio from the CDs using EAC, Exact Audio Copy software (free download), transcode the WAV files to FLAC, Free Lossless Audio CODEC, save them to the external USB HDD, and attach that to the SB Touch. Control it from its touch screen, or at a distance with its handheld remote, or with an application running on your Android tablet/smartphone, etc.

The notion of entry level should include some thought to upgrade paths, improvements to the system.

On the upstream side, the networked digital audio side, the SqueezeBox system is easilly expanded. You can attach the SqueezeBox Touch to a network and put the files on a server, making them available to other devices on the network, including addition of more SqueezeBox players elsewhere in the home. For a server, you can buy a suitable inexpensive NAS, or repurpose an obsolete PC with free software. That is in sharp contrast to the CDP, which is not something you would later attatch to a network.

Likewise on the downstream side, that SB Touch is a better foundation to build upon.

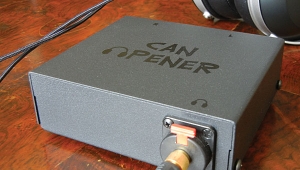

With either the CDP or the SB Touch, someone might later add an external DAC attatched to the S/PDIF coaxial digital audio output port. But unlike the CDP, the SB Touch can also use an asynchronous USB DAC, such as the ~$250 AudioQuest Dragonfly (requires the enabling application and the use of a powered USB hub).

Better yet, one could later attach the SqueezeBox Touch to the new ~$1200 Oppo BDP-105 multi-format optical disk player, which adds SACD, DVD-A, and BluRay compatibility while also having an excellent DAC. The Oppo BDP-105 is not just an optical disk player, but also has digital inputs including asynchronous USB, coaxial S/PDIF, and optical Toslink, allowing it to be used as an external DAC for other devices.

Standalone CDPs are dinosaurs whose time has already passed, though many (myself included) still have them in playback setups, those are quickly becoming far less usual, going toward novelty, like mini disc players, digital compact cassettes, cassette decks, etc. Buying a new one now is a waste of resources better spent elsewhere.