| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

...in this 2010 C-SPAN interview talking about Charlie and the book, starting at 40:50.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tv0ingTSKYo

If you have time, the whole wide-ranging interview is worth it. Stanley's observations could have been made today.

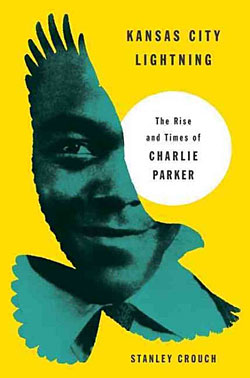

Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker

by Stanley Crouch (New York: Harper, 2013), 365 pp. Hardcover, $27.99.

Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker

by Stanley Crouch (New York: Harper, 2013), 365 pp. Hardcover, $27.99.