| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

..in the sudden absence of $10K from my bank account

But, as I described in last month's column, the cantilever of an ideal phono cartridge would be as short as possible, with a fulcrum equidistant from the stylus at one end and the generator at the other: Otherwise, the generator's excursions can't really keep pace with the excursions of the stylus, the result being compressed music. And compressed music is on a par with condensed soup, evaporated milk, and freeze-dried coffee: All are 20th-century substitutes suitable for use only in times of war.

Thus does consumer friendliness come at the cost of diminished fidelity—a commodity to which the mainstream audio press has, for decades, paid the most extravagantly self-serving lip service. Sure, frequency-response aberrations have always come in for their share of finger-wagging, but in the 1960s and '70s, when the faithful reproduction of dynamic contrasts was thrown out the window as cartridge manufacturers competed to achieve ever-higher levels of "trackability" at ever-lower levels of vertical tracking force (VTF), what did we hear from the old-guardians of fidelity?

[Crickets]

Life during wartime

When is a long cantilever better than a short one? I can think of only one hypothetical situation, and that would be if the generator's moving parts—its coils, magnets, nub of iron, whatever—were attached directly to the stylus end of the cantilever. In such a case, a cantilever of any reasonable length could be used: The location of its fulcrum would now be irrelevant.

Yet that situation isn't hypothetical: It's precisely what one sees in the Neumann DST 62 phono cartridge, which the famous Berlin-based maker of microphones introduced in 1962. In that regard if no other, the Neumann stands alongside the Decca/London cartridges I discussed last time as a rare shot across the bows of audio asininity.

You can pretty much guess the rest of the story: The DST 62 was an exceptionally good product, but Neumann didn't sell many of them, perhaps because the thing was so difficult to make, and so expensive: When first imported into the US, it sold for $79.50—in 1962, a great deal of money for a phono cartridge. The DST 62 appears to have been phased out by 1966, but in the late 1980s it was rediscovered by hardcore enthusiasts in Japan—the same people who rediscovered the horn loudspeaker, the 300B triode tube, the turntable idler wheel, Scotch whisky, and Lark cigarettes. Today, vintage enthusiasts worship the groove the DST traces, and samples, when they surface, command huge prices.

In fact, it was a Japanese maker of cartridges that, not long ago, cooked up a modern model based on the basic DST 62 design: The Lumière, available as both a self-contained pickup head and a standard-mount (0.5" spacing between the bolt holes) phono cartridge, attracted vintage enthusiasts with its Altec-esque green hammertone finish and its promise of Neumann-esque sound. But it seems that relatively few samples were made, and descriptions of the Lumière's impressive performance are tempered with reports of considerable sample-to-sample variation. Besides, no one seems to know for sure whether the Lumière remains a commercial reality. (Either way, I have to keep an open mind: Like most other hobbyists, I've never even seen a Lumière cartridge, let alone heard one.)

Fast-forward to April 1, 2015, when Robin Wyatt, of Robyatt Audio, sent me an e-mail containing no text and a single image: a photograph of a cartridge I'd never before seen, the body of which appeared to be a big, bland block of aluminum. Closer inspection revealed a familiar-looking—and very long—cantilever, poised between a pair of outsize and similarly recognizable pole-pieces. Was I looking at a DST motor in a brand-new body? My four-word reply: "You have my attention."

I could not have anticipated Wyatt's response: "Siberian remake of the famed Neumann DST. And guess who the importer is?" (footnote 1) A later e-mail explained that this new manufacturing company is called Tzar Audiology, but of the individual doing the actual building, Wyatt said that "he would rather remain anonymous." (But: He let it slip that the builder is a male!)

News, on April Fool's Day, of a presumably expensive Siberian product is typically met with disbelief. But years of reporting on perfectionist audio have beaten much of the skepticism out of me. I wrote back and expressed my fervent interest in borrowing a review sample, which I received from Robyatt Audio at a time when the Mets were doing especially well in the National League East. Life was good.

Wish upon a Tzar

Arguably the most sinister horseman of the hi-fi apocalypse is the one called Excess Mass (footnote 2). Thankfully, one product category has long remained immune to his villainy: No one has ever found a way to fasten a great, steaming, 30-lb pile of aluminum to a phono cartridge.

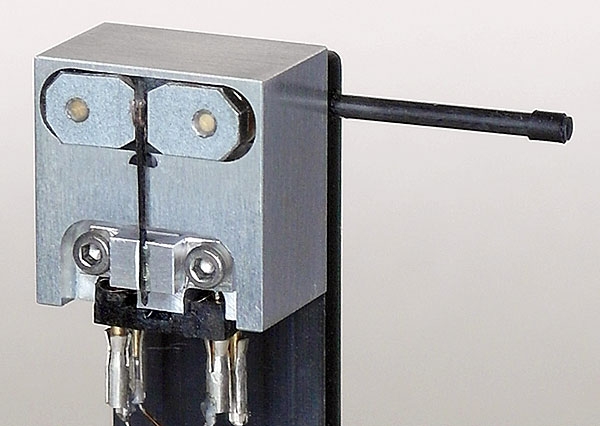

Nevertheless, the Robyatt-imported Tzar DST ($10,000) is by far the heaviest phono cartridge of my experience: It weighs a remarkable 17.5gm—that's just 0.1gm less than an entire EMT TSD 15 pickup head—and its aluminum body is 0.83" (21.3mm) long by 0.81" (20.7mm) wide by 0.51" (13.1mm) tall. That the latter two dimensions approximate the so-called Golden ratio did not escape my notice. (Who says modern audio reviewers don't know how to measure?) The body's top surface is machined with a pair of holes, spaced 0.5" apart, drilled and tapped for cartridge-mounting bolts of the usual sort. An opening for the Tzar's magnet and intricate pole-piece structure is milled into its underside, along with a recess for the block, evidently adjustable, to which the cantilever is mounted.

In a departure from the original Neumann DST 62, whose cantilever was an aluminum tube, the Tzar DST's cantilever is a rod of solid carbon fiber 19mm long and, over most of its length, perhaps 0.5mm in diameter (a guess). The rod's compliance, such as it is, is defined by two elements. The first is a tiny, thin, U-shaped elastomer damper between the rod and the cartridge body, approximately 7mm behind the stylus. The second element is somewhat more radical: At a point along the cantilever's length just ahead of the aluminum block to which it's fastened, a relatively healthy amount of carbon fiber has been milled away on opposing sides of the rod—imagine a pair of tiny cartoon beavers felling a tree—leaving behind only a very thin segment of rod for about 1mm of its length.

The stylus, which is said to have a spherical profile, is fastened to the cantilever with an adhesive that looks epoxy-like, applied in what seems a slightly more generous amount than one usually sees. (I assume that drilling the carbon-fiber rod with a hole for the stylus shank is not feasible.) And then we have the coils, which are directly affixed to opposite sides of the cantilever. While the coils of most moving-coil cartridges are circular or elliptical, these are equilateral triangles, installed without a former at their center: They function as air-core coils. Each triangular coil has rounded apexes and sides ca 2mm long, and each is affixed to the cantilever so that the triangle's forwardmost apex is just behind the stylus, and its side nearest the record surface is parallel to and slightly proud of the carbon-fiber rod. Thus, with the stylus seated in the groove, there is a vanishingly small gap between vinyl and coil.

From all appearances, making a Tzar DST cartridge is only slightly easier than injecting dinosaur DNA into frog eggs. I have steady hands and decent vision in one eye, and I'm pretty good at detail work—yet I know I couldn't even begin to do this sort of thing. If the foreman on the DST assembly line gave me 40 tiny rods and told me to whittle away a smidgen of carbon fiber from each, he'd be lucky to get back 80 even tinier rods. I'd surely lose my job. I might even get packed off to Siber—

Oh. Never mind.

Bring him home

A watchmaker's expertise is obviously called for here. Not at all strangely, it was a watchmaker who came up with this whole let's-rescue-the-DST-from-extinction thing in the first place: Frank Schröder, who also happens to be one of the world's foremost designers and makers of tonearms.

Footnote 2: His no-less-evil companions are Inefficiency, Juvenile Styling, and Pointless Complexity.

..in the sudden absence of $10K from my bank account

Or is anything for that price just wrong to you (ironic from a shameless cheerleader of things BMW, and more strange, someone who buys these vehicles and doesn't appreciate the precision craftsmanship here)?

If so, why read this review other than to be negative and disappoint music lovers with simplistic derision?

Another great review from one of the best writers extant.

Hi Art,

I was wondering if you have ever heard any of the original Neumann DSt cartridges? Reason I ask is that while the Lumiere was touted as a DSt copy, sonically it had nothing in common with Neumann. Do you know how the Tzar compares to the original sonically?

david

I'll have to say only Art Dudley can make reading about a product I have absolutely no interest in an enjoyable experience.

Hi David. In answer to your question, only once, and not in my own system. Then—as now, with the Tzar—the lasting impression was of uniquely realistic touch: an aspect of playback quality that matters to me now even more than it did a year ago (danged if I know why). I don't have any recollection whatsoever of the original's tonal balance—but, given the unfamiliarity of the system in which I heard it, I doubt if any recollections along those lines would be relevant, anyway.

[the lasting impression was of uniquely realistic touch: an aspect of playback quality that matters to me now even more than it did a year ago (danged if I know why).]

I have 3 DSTs that I bought NOS, 2 are early versions and 3rd is a DST 62, the tonal depth, timbre and balance are completely natural and part of the realism that you mention. In addition to that there's a heft and solidity to the sound which is closer to real instruments than anything else I've ever heard. A properly working Lumiere had a beautiful and delicate sound but nothing of the realism and timbre of a DST. A distant 2nd and also favorite cartridges with similar sense of realism are the EMT OFD as you mentioned, early Ortofon SPU with associated SUT and the wonderful SL-15T. There are many great modern cartridges that do so many things well but I haven't any with the same sense of realism of the ones mentioned above. Thanks for the review, I'll try to find a Tzar to audition and see how it compares, hopefully quality with be up to par too.

. . . thank you, Glotz and John W, for your very kind comments.

is that a BMW has an intrinsic value as a consequence of it's performance and function that makes it worth the price.

A 10,000 dollar phono cartridge does not because 99% of it's performance quality can be had for 1/10th the price.