| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

It seems to me that the comments on classical music albums are far less than comments on equipments. Audiophiles are, again it seems to me, more into exotic electronics than wonderful music itself.

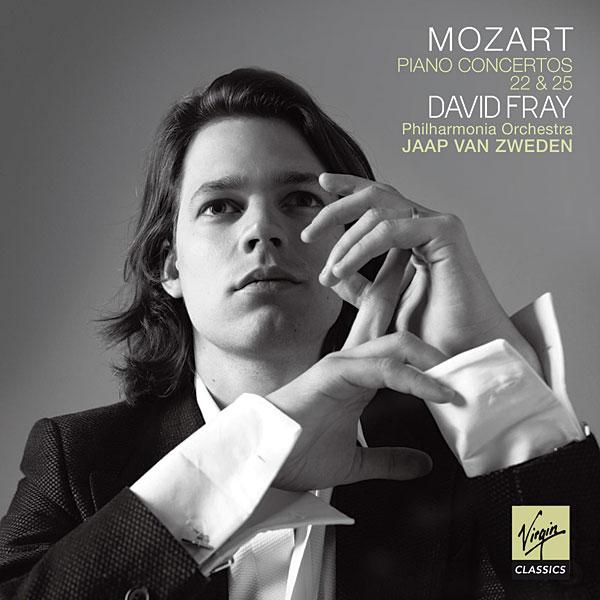

I have not heard this album yet, but I have David Fray's Bach Piano Concertos CD. That album has already demonstrated Fray's excellent skills and unique interpretation, and it thoroughly impressed me. If he keeps the current trend, he will be someone to watch out.